The Pulpit and the Pen is moving to a new site to better reflect my new situation as I move to the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. Check out and bookmark From A Rocky Hillside.

The Pulpit and the Pen is moving to a new site to better reflect my new situation as I move to the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. Check out and bookmark From A Rocky Hillside.

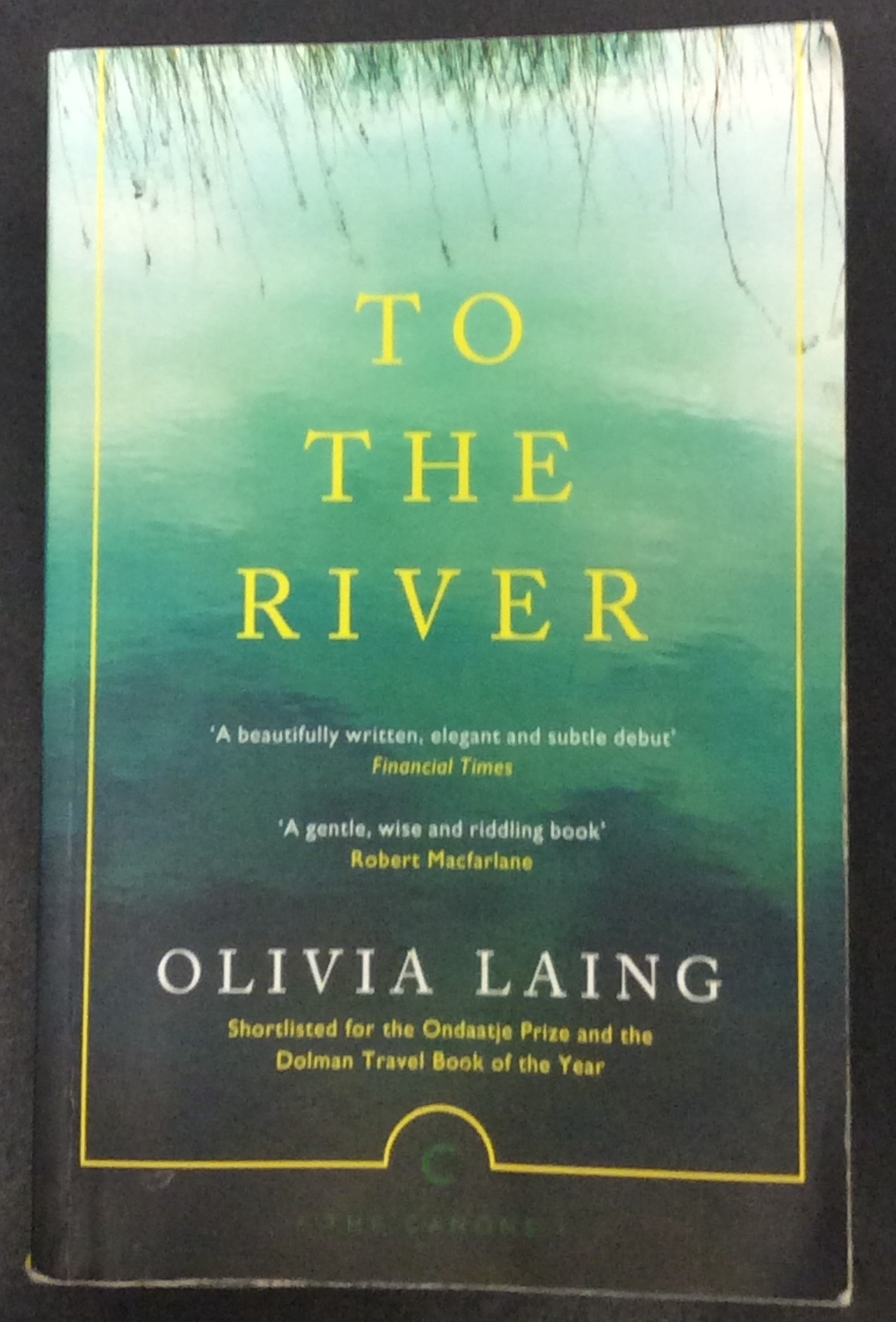

John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History (2004, Penguin Books, New York, 2018), 548 pages, some photos, index and notes.

This is an impressive book that does more than just provide a history of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Barry provides a history of medicine especially in the United States, of the science around disease’s transmission, and of how all this came to play in the pandemic that struck the world at the end of World War I. He even suggests that the disease may have shortened the war and may have led to its disaster the followed in which set the stage for the Second World War. The war ended after German’s last great offensive was unable to be continued because too many German troops were ill and unable to sustain German’s advance. In the negotiations afterwards, it appears that many (including Woodrow Wilson) may have battle with influenza (which may have played a role in his stoke). Wilson’s absence and lack of focus toward the end of the negotiations certainly hindered his ability to keep the French imposing punitive measures on Germany.

In an addition to providing background history to the medical profession and the science of disease (which sometimes became confusing to me as a layperson in this area), Barry also describe the transmission of the disease from birds to humans and other animals (especially swine). One it’s in the body, he describes our natural immune response. Interesting (and frightening) is that this strain was so dangerous in younger patients whose immune systems often overreacted and caused a faster death. He also pointed out that most of the deaths weren’t directly from the flu, but because the flu opened up pathways for other infections, especially pneumonia. (This is something that is enlightening in the current COVID-19 debate, as there are some who say that only those who died of COVID only should be counted as a COVID death. Most influenza deaths were not from the flu but from pneumonia).

No one knows for sure where the pandemic began. Although it became known as the Spanish flu, it is certain that the flu didn’t begin there. Spain was relatively late in being attacked by the flu, however since Spain wasn’t at war (unlike the United States, Great Britain, France, Germany and Italy), there was no censorship of the press in Spain, so people often associate the flu with the country reporting the flu. The other countries in war censored the information about the flu to keep information from their enemies even though all armies (and countries) were battling it at the same time.

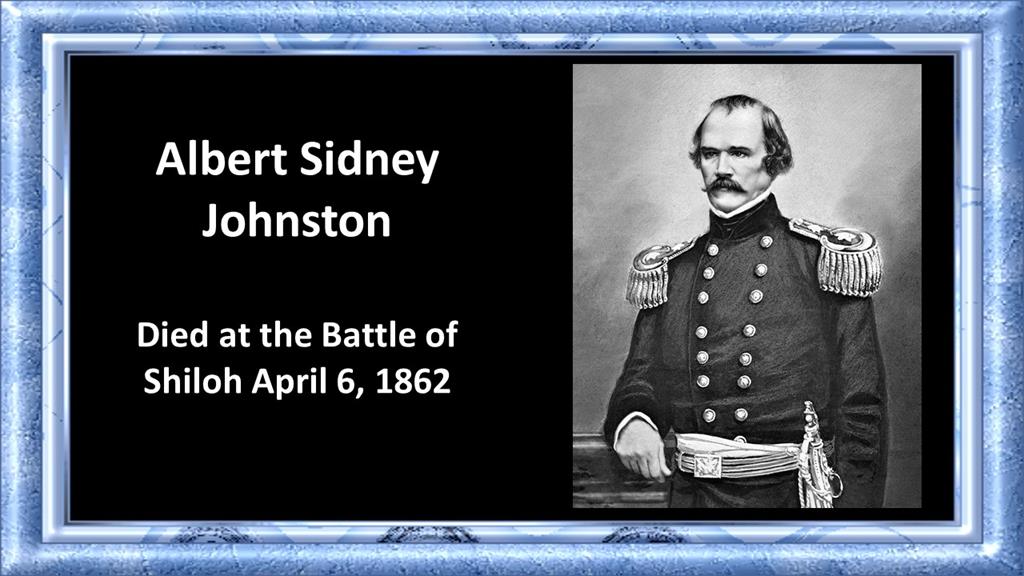

One theory is that the flu began in Kansas, which had a similar illness in pigs. As those from the area were drafted into the army, they brought the illness into induction centers. Early on, the army was battling the flu. The army, as it began to mobilize after the United States entered the war, began to move personnel around the United States and to Europe. Interestingly, all medical personnel with the military knew the danger of illness being spread by armies (and early on sought to minimize the danger of measles). The disease also travelled in waves, starting in the spring of 1918. The peak was in the fall of 1918, but it kept moving and slightly changing. There were people who caught it more than once, although most who survived an early attack had protection against later attacks. It is also thought that the virus became less lethal in each wave.

Another reason this outbreak was so deadly is that the army sucked up the best doctors and nurses in the country, which left older and ineffective physicians treating civilian populations. The military (and others) passed the disease off as “just influenza” and wasn’t willing to stop the movement of personnel as a way to prevent the disease spread. However, late in the war, they did postpone drafts because the military was having a harder time trying to care for their own ill and were incapable of processing new recruits.

Just as in the current COVID crisis, many places in which influenza was rampant shut down gathering places, including restaurants, bars, churches, and theaters. The lack of knowledge was especially daunting (caused by censorship that kept anything that might slow the war effort down). This led to panic and in many places, people refused to help those in need out of fear of catching the disease. The deaths numbers in some places (especially parts of the world without much natural immunity to influenza viruses) were horrific. Fifty million and perhaps as many as a 100 million worldwide died at a time when the world’s population was 1/3 of what it is today.

I recommend this book, especially now, when we are dealing with another pandemic. The parallels are frightening, and this book could help clear up a lot of the misinformation that abounds today.

Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

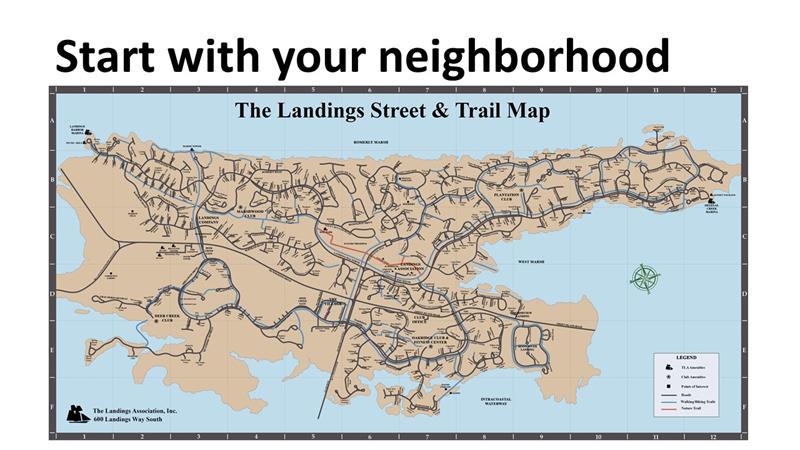

Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church

September 20, 2020

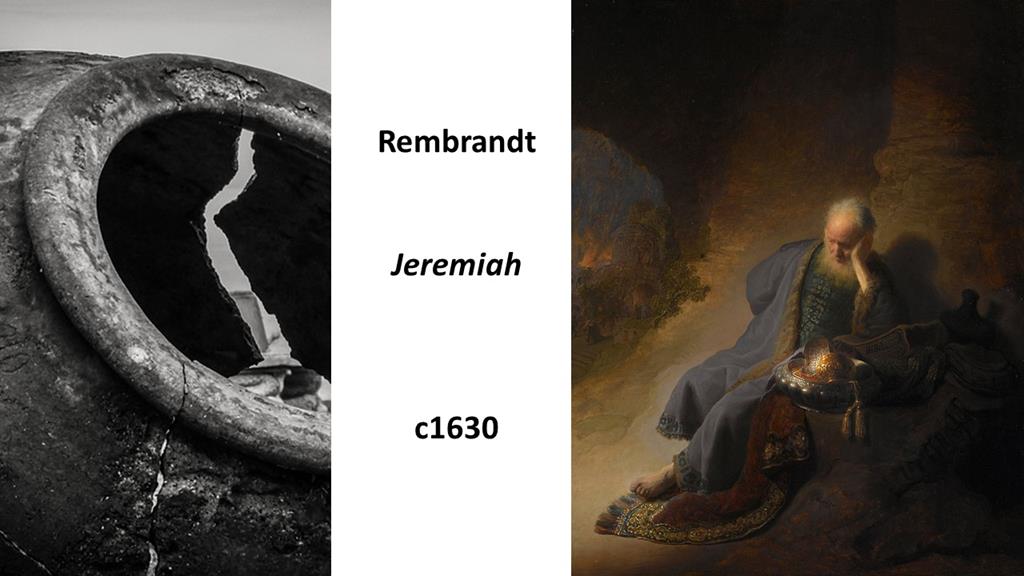

Jeremiah 29:4-14

To watch this service on YouTube go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pKiTvhFZ3Sk. If you just want to catch the sermon, go to 18:40, where I began with the scripture reading.

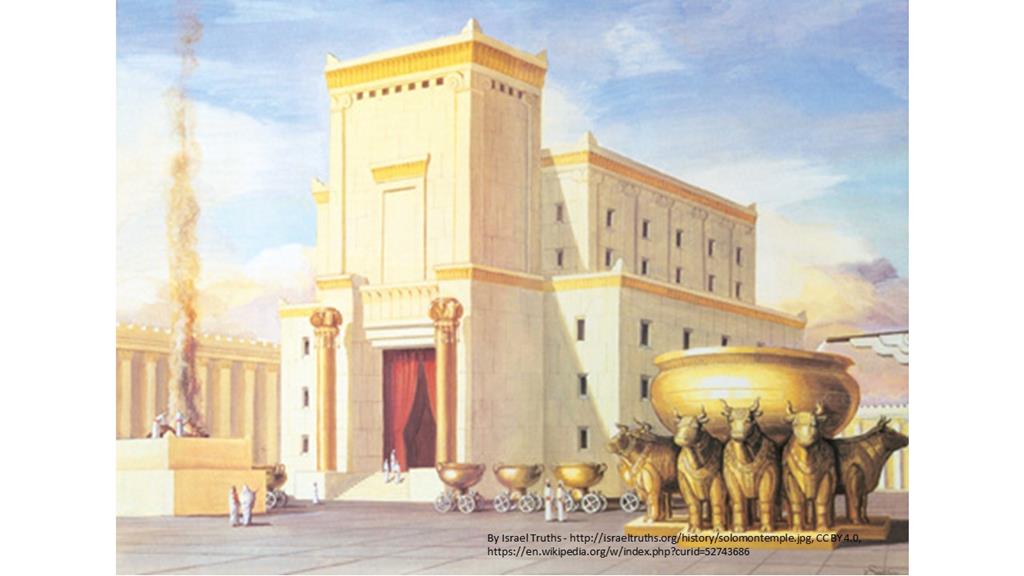

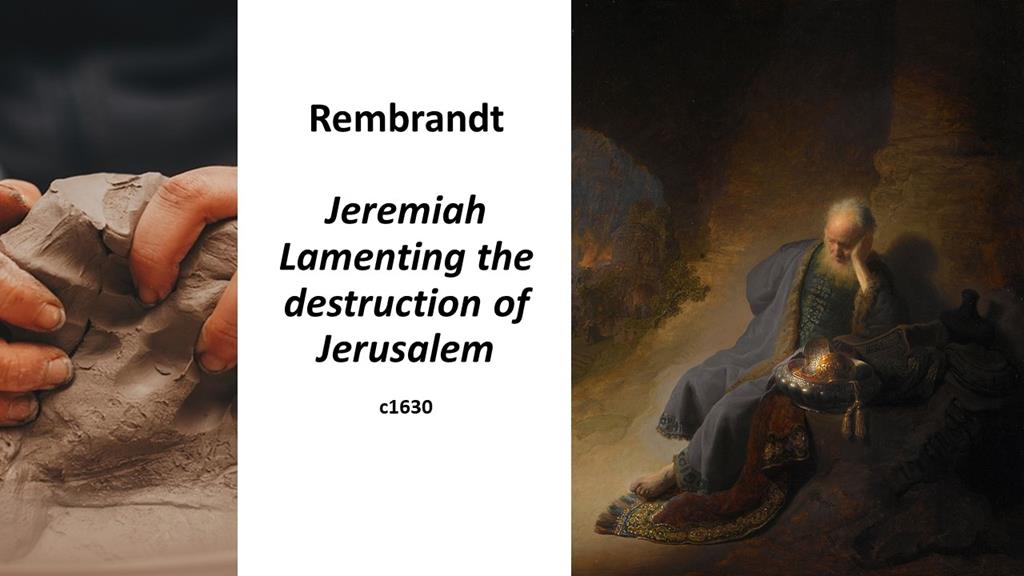

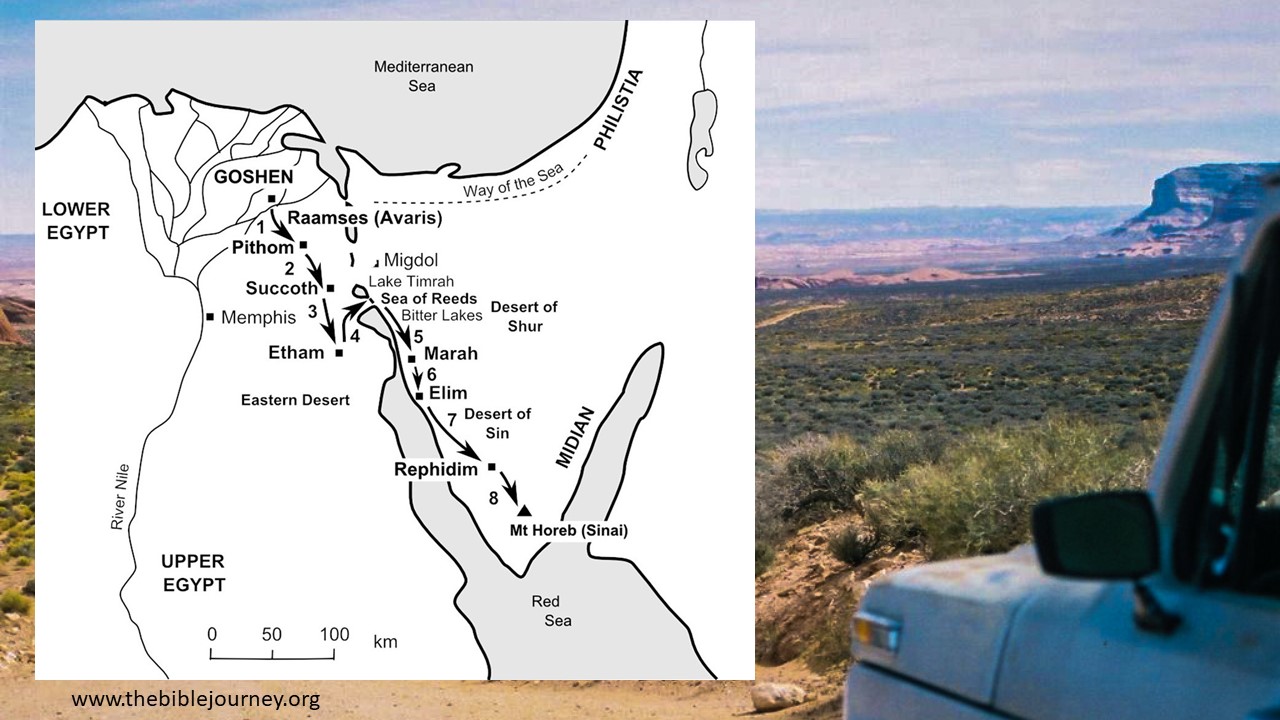

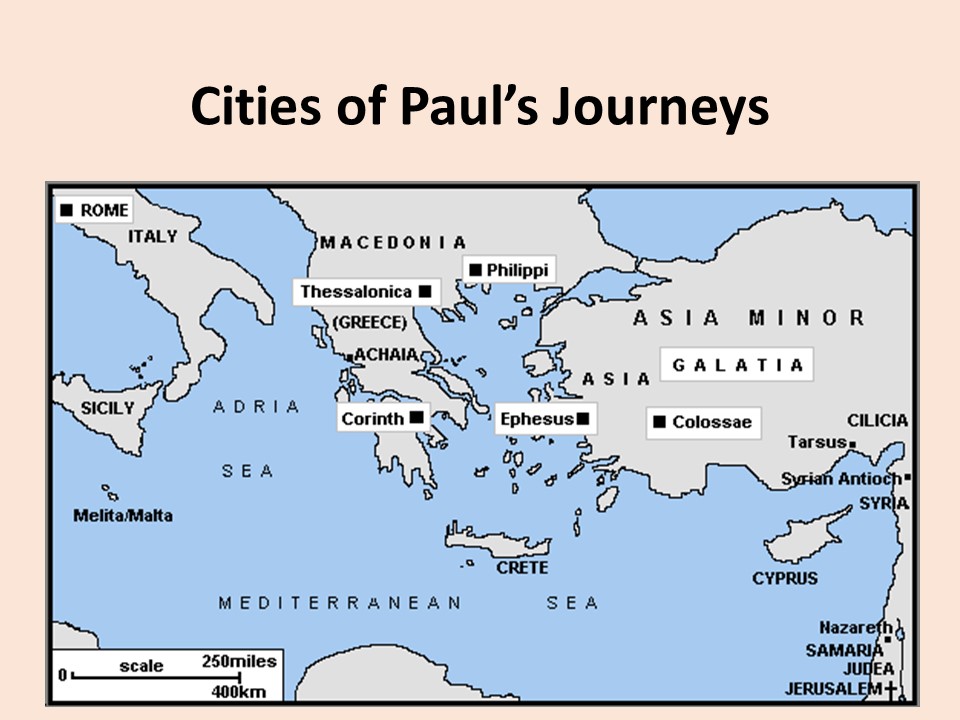

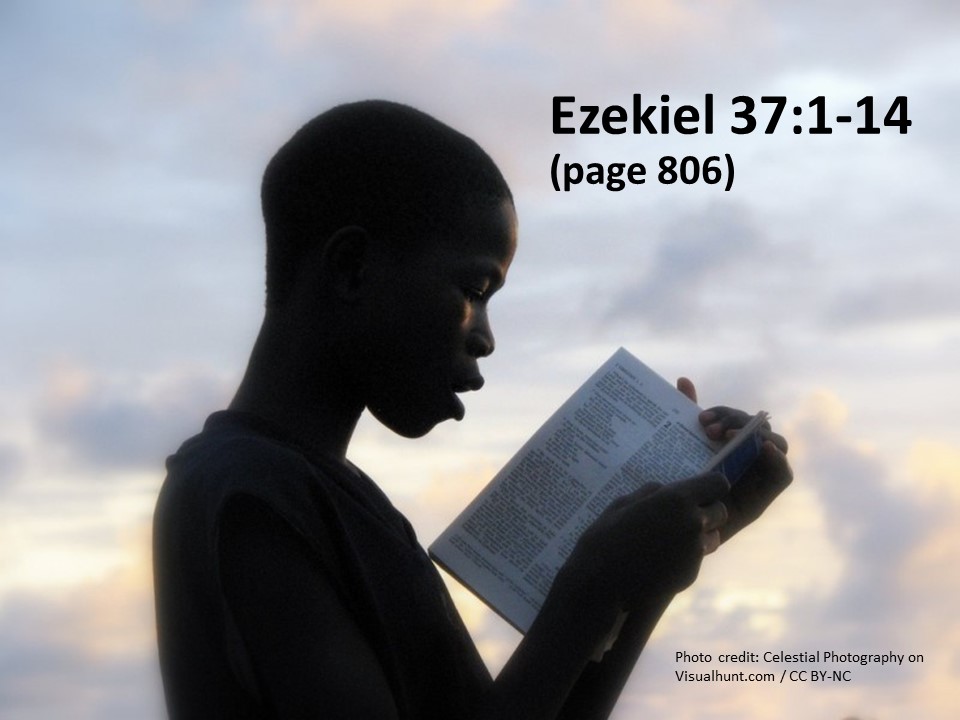

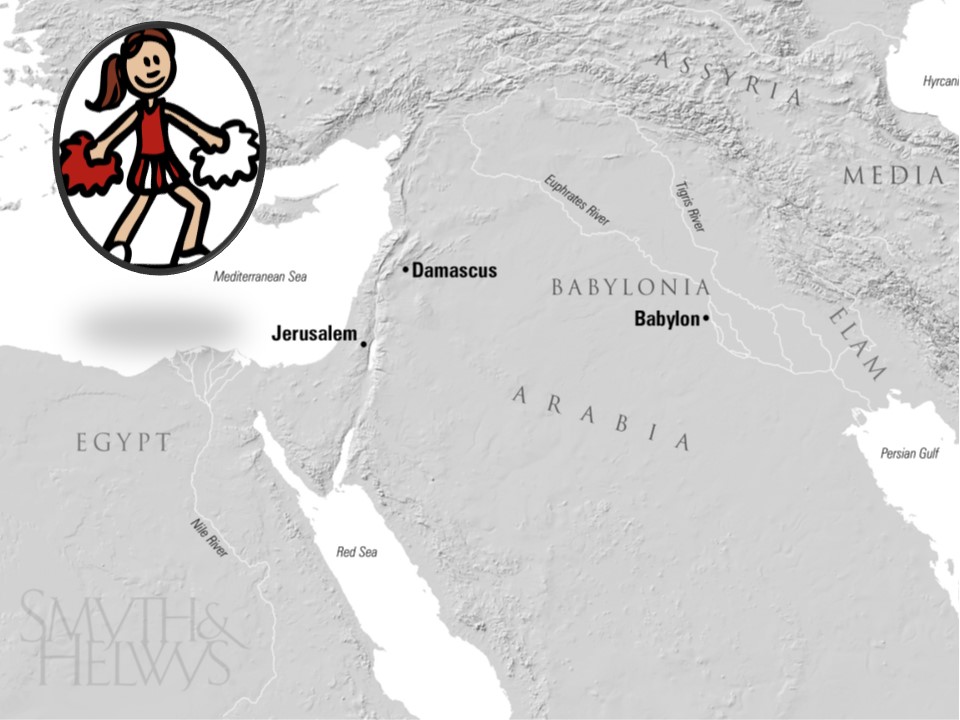

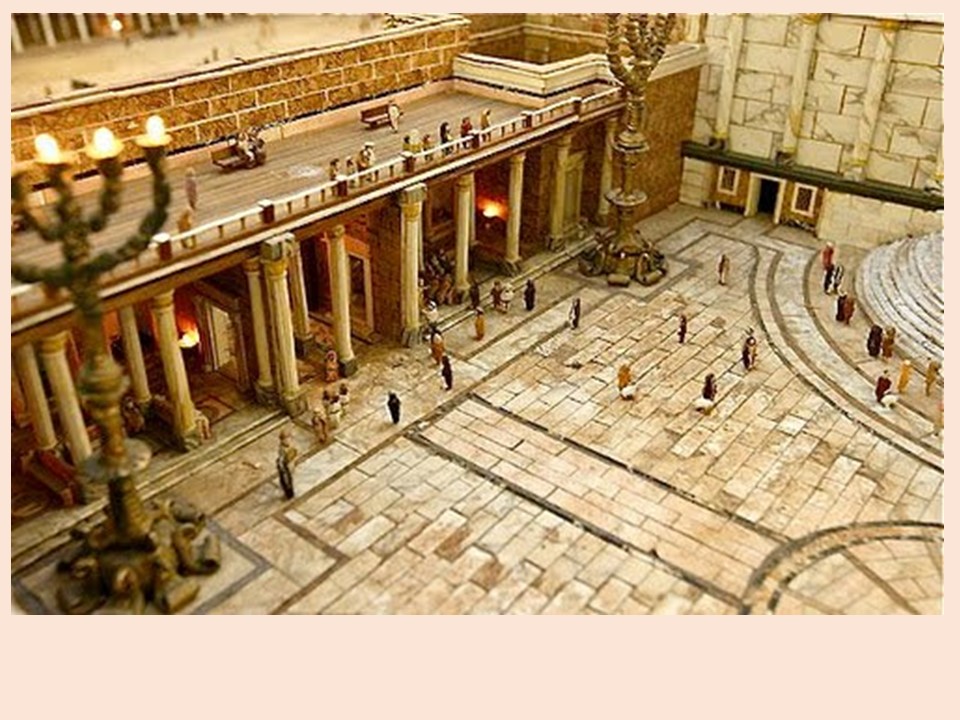

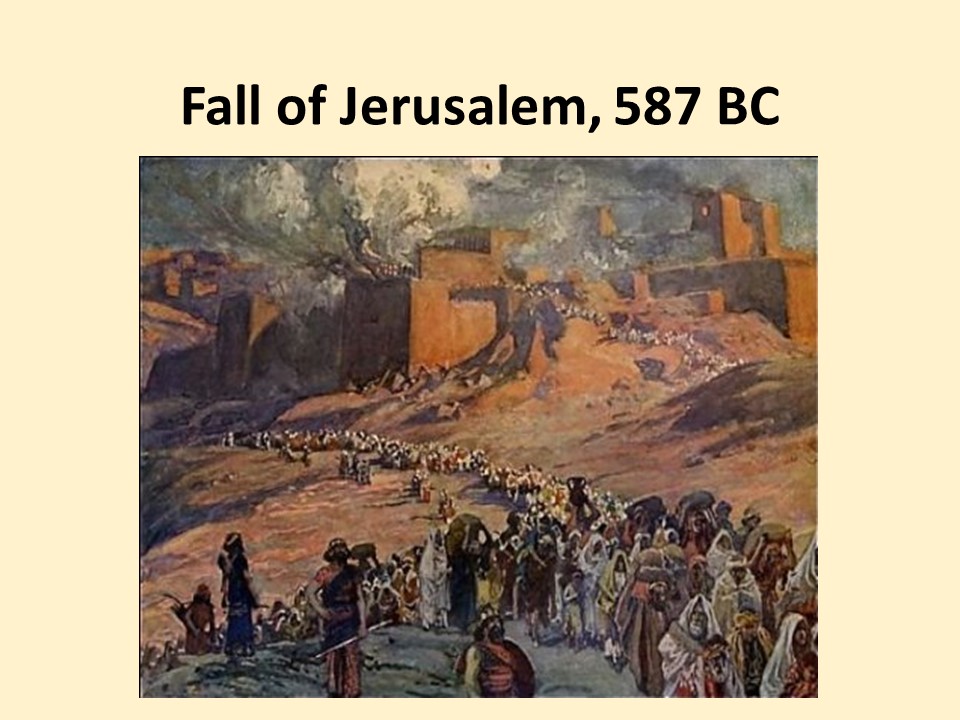

If you know Old Testament history, you’ll recall there was a period in which Jerusalem was a vassal state of Babylon. In 597 BC, the Babylonians took large numbers of leaders from Jerusalem, along with skilled craftsman, into exile to Babylon. It was an attempt by this world power to keep Jerusalem in line by making connections between the two nations. But the Hebrews kept revolting against Babylon and in 586 BC the city was destroyed, the temple burned and those who survived the slaughter were either led into exile in Babylon or fled to Egypt.

This passage takes the form of a letter Jeremiah writes to those already in exile in Babylon. It was written sometime between 597 and 586 BC, between the first great exile and the last.[1] At this time, in Jerusalem, there is a lot of nationalist talk. The people are sure God will protect his temple and nothing serious would happen to them.[2] Unlike Jeremiah, I’m sure others wrote subversive letters to those in exile, encouraging them to do what they could to destroy Babylon’s ability to make war.[3] But that’s not Jeremiah’s message. Instead, he tells those in exile to make the best of the situation. That if Babylon prospers, so will they. That’s not what people want to hear. Many think Jeremiah is a traitor, that he’s aiding the enemy.

You know, like those in Babylon, we’re now living in a time of exile. Things that we took for granted back in February and early March have been snatched away. We want Good News, we want to know when this nightmare is going to end. But is that the right question to be asking? Maybe we should be listening to the advice of Jeremiah and make the best of the situation in which we find ourselves?

I was reading a blog post this week in which the author, the president of the Barna Group, a religious think tank that also does polling, wrote about ways the pandemic is negatively impacting people. Barna’s polling had shown that relationships in America were in trouble before the pandemic. After five months of living in lock-down, it’s worse and creating a mental health crisis. Loneliness is a problem, not just for older people who live alone. Surprisingly, its worse for those younger. Two out of three millennials say they are lonely at least once a week. Relationships are straining under the pressure we’re facing, and addictions are growing.[4]

At a time like this, we want to hear that the pandemic will soon be over, that things will be returning to normal, or that it’s really not as bad as we’re making it out to be.[5] And there are those who tout such messages, but are they any different than the prophets of Jeremiah’s day who suggested things are going to be okay? Time will tell, but the message of Jeremiah still applies. We are to make the best out of our present situation. Time goes on. We can’t stop making a life for ourselves which Jeremiah describes as building houses, planting gardens, marrying off children, starting families, and working for the wellbeing of the city in which they live. In other words, while we take care of their own needs, we’re also to help care for others, even those who believe differently than us.

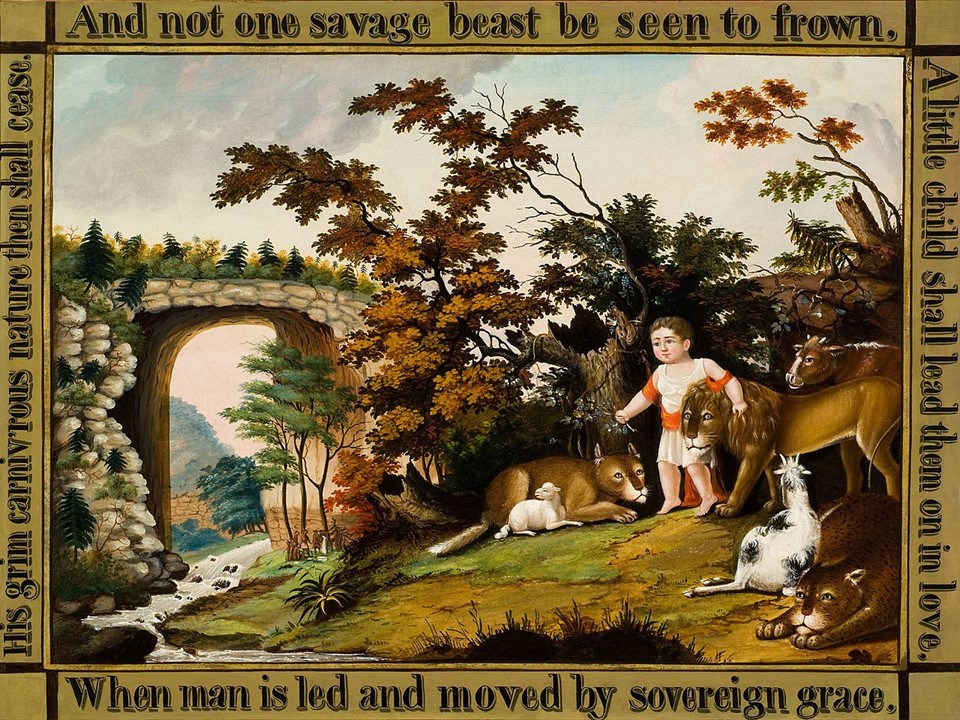

This all leads up to the 11th verse, which is a favorite of many people. “For surely I know the plans I have for you, says the Lord, plans for your welfare and not harm, to give you a future with hope.” Many people will copy this verse in cards sent to grandchildren and I’ve even heard graduation speeches built around these words which assure us that God wants what is best for us. God promises his children a hopeful future.

As comforting as this verse sounds, we must place it in context. In verse 10, just words before these, those in exile are reminded that they are going to be there for some time… 70 years! That must have hit like a bombshell. Those in exile are sad and missing their families and their community and the temple, the symbol of their God. They want to go home. In this sadness, Jeremiah encourages them to seek the welfare of the city in which they will find themselves, a place that they hate. It’s good advice, but in some ways it’s tough love.

As I’ve said, the purpose behind this exile, for the Babylonians, was to take enough of the leadership, including many of the young promising leaders like Ezekiel and Daniel, to ensure that Judah wouldn’t revolt. In a way, although they did not know it at this point in time, those who were first taken away had it easier than those who stayed behind. Those still in Jerusalem experienced the hunger and the horror of the destruction of Jerusalem a decade later.

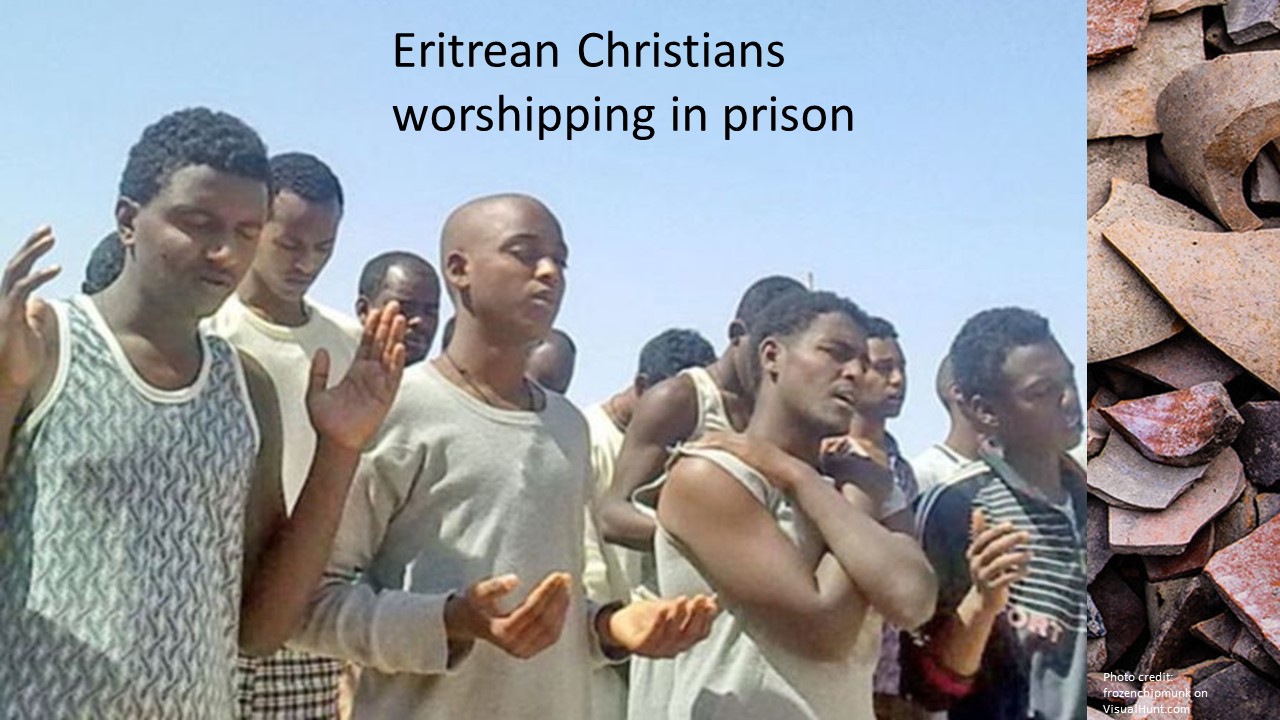

This was not a good time in Israel’s history and in a way it’s not a good time in our history. As a nation, Israel was being torn apart and the same can be said to be happening to us. Back then, people were afraid. Today, we’re afraid. Back then, famine, suffering, more death and more destruction were on the horizon. We don’t know what’s on the horizon, but the dying from COVID is not over and our society seems to be splintering into factions. But as people of faith, we are to have a positive outlook for we know that God is in control and while God’s timing often doesn’t correlate with our desires, God does work things out.

Faulkner, the southern writer from Mississippi, once said that while it’s hard to believe, “disaster seems to be good for people.” When entering a period of exile, like we’re in, much of what is superfluous is stripped away and we learn what really matters. What matters is that we seek God and trust in God’s promises.[6]

Consider this passage. Even as darkness was descending on Israel, God speaking through Jeremiah offers a word of hope. To know that even though things are bad, God has our back and in the long-run our best interest at heart can help us endure great challenges. The people of Israel had to learn over and over again to be patient. We need to remember that and trust God.

Yes, we are in trying times. But this is not the first time God’s people have faced challenges. The good news is that when we endure and remain faithful, our faith is strengthened. As Paul captures so elegantly in the fifth chapter of Romans:

We boast in our suffering, knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit that has been given to us.[7]

May our lives be filled with love and hope despite what we experience in life. Amen.

©2020

[1] J. A. Thompson makes the case that this letter was written around 594, after some of the exiles created disturbance in Babylon that lead to at least the execution of two exile members of the Hebrew community there. See J. A. Thompson, The Book of Jeremiah (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1980), 544.

[2] The Prophet Ezekiel, who was a part of the early exiles, had a vision in Babylon of God leaving the temple which helped prepare those there for the temple’s destruction. See Ezekiel 10.

[3] A hint of this can be seen in the rest of this chapter which concerns a letter from Shemaiah in Babylon telling the high priest in Jerusalem to silence Jeremiah. Jeremiah’s prophecy is not what they want to hear. See Jeremiah 29:24-32.

[4] See https://careynieuwhof.com/new-trends-4-ways-the-pandemic-is-negatively-impacting-people/

[5] An example from the past: In the 1918-19 influenza pandemic, many kept saying “it’s only influenza” while more people died (in sheer numbers, not in percentage of population) from the illness at any other time in history. See John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History (2004, Penguin Books, New York, 2018).

[6] Eugene Peterson, Run with the Horses: The Quest for Life at its Best (Dowers Grove, IL: IVP, 1983), 156. Peterson’s Faulkner quote comes from Lion in the Garden, Interviews edited by James B. Merriweather and Michael Millgate (NY: Random House, 1968), 108.

[7] Romans 5:3-5.

Grand Cru approaching the mark just ahead of us

The finish was exciting. An offshore breeze was blowing steadily toward the land and many of the boats still in the race were all convening on the R2W buoy two miles off Wassaw Island at the same time. There was only one boat left in our class, Todd’s Grand Cru. While we had opted to stay further offshore in the hope of finding wind, Todd and crew hugged the shore. So, the end of the race had us approaching the mark on a reach, while Todd, who had to tack back toward the mark, was close-hauled, a sail position that gave him more speed. However, he also had more distance to cover. We’d thought we were easily going to make the mark first, but as we both moved closer to the mark, we could tell that Todd was really moving. We checked the sail trim and did everything possible to increase speed, but they beat us, rounding the mark a couple boat lengths ahead. But it didn’t matter. We still won when they factored in the boat’s handicap. Grand Cru is a 33-foot boat and has a much higher handicap than our 24 foot boat. He’d have to finished 20 minutes before us to have won the race.

We crossed the mark at 6:02 PM. It had been a long day and we still had seven miles to go to reach the marina. That was where the final mark was supposed to be but since there had been so little wind and race rules stated that everyone had to finish by 7 PM, which would have meant that no one would have finished, the shortened the race late in the afternoon. The race committee had even headed end, leaving each boat with the instructions to cross the buoy to starboard, turn north and when you pass the buoy, to call in the time. Most of the spinnaker boats (we sailed in the non-spinnaker class) still in the race finished around the same time. None of the cruising class boats finished the race, all having opted to abort earlier in the afternoon.

Steve setting a course with Doug P at the helm as we sail to Hilton Head

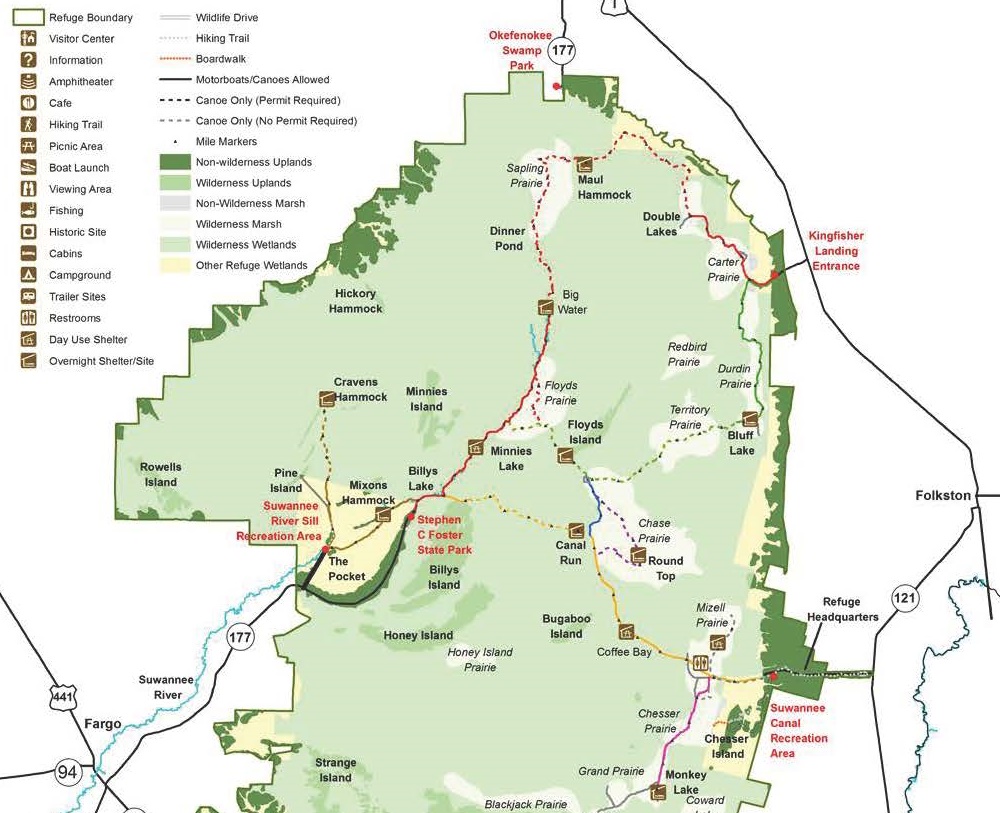

Our race weekend started on Friday, when Doug P., Steve and I took our boat, Bonnie Blue, out to sea and up to Hilton Head’s Harbour Town. We left Landings Harbor Marina at 9:45 AM. The forecast called for light wind and we were thinking we might have to motor most of the way up, but as we got the boat out of the marina, the winds picked up and we were able to sail on a reach (wind coming off the beam or 90 degrees to the boat’s direction), without ever changing tack, all the way out of the Wilmington River and Wassaw Sound. Once we were in the ocean, the winds continue from behind, allowing us to run wing-to-wing (the mainsail and the jib on opposite sides of the boat to catch the wind from behind) all the way north, pass Little Tybee and Tybee Island while sailing down waves that were moving favorably in our direction. Once we crossed the shipping channel to the Savannah Ports, we turned inland toward Daufuskie Island (the setting for Pat Conroy’s memoir, The Water is Wide), sailing across Calibouge Sound until we picked up the channel markers that led us behind Hilton Head Island. The wind died about the time we made it behind Hilton Head and, for the first time since motoring out of the harbor, we engaged the motor and found our slip at the Harbour Town marina. On Hilton Head, the fourth member of our team, Doug B, who’d been spending a few days with his family on Hilton Head, met us and drove us back to Skidaway.

Leaving Harbour Town

Saturday morning began early as we all gathered before daybreak to drive back up to Hilton Head. The sun was rising as we crossed over the Savannah River bridge. By 8:30 AM, we had the boat ready and motored out to the start line between Daufaskie and Hilton Head. The first class, the cruisers, were to begin at 10 AM. By then, all boats were in the area and they began the countdown sequence. The tide was running in, strong, and what winds there were came from behind, make it a downwind start (you generally start upwind, as you can make faster speeds).

Cruiser class approaching the mark

At four minutes before the starts, all the boat were required to kill their motors. They did, then then wind died, and the cruisers (there were only three) were pulled further and further from the starting line. A minute before the start, they cancelled and waited a few minutes before going again into the six-minute sequence. The same thing happened. The race chairperson then suggested that the boats motor to out beyond the starting line and let the tied pull them back inside it before the start. On the third attempt, they had a start. As the cruising boats tend to be slower, they were given ten minutes or so headway before they began the second flight, those of us not racing with spinnakers.

Thankfully, our start went off without a hitch and by 10:45 AM, we were racing, but without a lot of speed. We tried everything, from going wing-on-wing to tacking and running on a reach. It was slow going, but within a few hundred yards of the start line we had passed the cruising class boats. Soon, the spinnaker class boats started and we were all bobbing around in Calibogue Sound, waiting for a puff to move us a little closer to our destination. It seemed to take forever. We kept looking at the same houses on Daufuskie and the marks in the Savannah River were so far ahead. We watched several container ships make their way out of the harbor and then others make their way into the harbor. Thankfully, without wind, the sky remained gray, reducing the sun and the heat.

a distant ship leaving Savannah

Around noon, we had a short burst of air that allowed us to make our way out of the sound and point eastward, toward the G5 buoy at Tybee Roads. We weren’t making great time, but at least we were moving, which continued until we made the turn south, toward Wassaw Sound. Then the wind died again. It seemed to take forever for us to cross the shipping channel. We had seen many ships in the morning, but thankfully while we were bobbing around in the channel, there were none. Finally, we reached the port side marks, putting us safely out of the channel and began to make our way south. Doug B pulled out his fancy binoculars, which allowed us to see well ships that were coming into port, but not strong enough to make out those bathing on Tybee, some two miles to the east. For what seemed to be days, but was only four hours or so, we keep the Tybee Lighthouse directly off our beam. Occasionally, they’d be a puff and we’d make some forward progress (to where the slough that runs between Tybee Island and Little Tybee was parallel to beam), dropping the lighthouse toward our stern. Then the wind would die and we’d drift back. Pretty soon the lighthouse would be off our beam. We talked about all kinds of things, but the only thing I remember being said was by Steve when he announced: “It’s a flat as a millpond out here.”

Waiting on wind (Steve holds boom out to catch every bit of wind while I do the same on the pole on the genoa, Doug B looking at sail shapes while Doug P either is looking at his sail app on his phone or is praying…

The chatter on the radio was slim. Occasionally a boat would announce they were giving up the race. Then, around four, there was some discussion over moving the end of the race to the R2W buoy. Since not everyone was within radio contact, such instructions had to be relayed to those behind us. Then, as it got closer to five, the wind slowly began to build. Tybee lighthouse dropped off our stern and we began to pass Little Tybee. The wind picked up and slowly the miles to the buoy began to drop (which we could measure thanks to navigation apps). By five, the wind filled in and we were quickly making out way toward the mark, which could first be seen as just a dot in the distance and slowly became more visible as we saw Todd’s boat coming toward us off starboard. After a day of bobbing, we finally felt like we were racing.

Heading home (Wassaw to port)

After making the mark, the wind continued as we made our way toward Wassaw Sound. By now, the tide had turned and was coming in, giving us an extra boost. Once we cross the north end of Wassaw, the wind died again. No longer racing, we started our motor and began to putt in, supported by the tide. The inland waters were like a mirror and while we putted, we flaked the mainsail on the boom and secured it with the sail cover. Then we rolled and bagged the geona (foresail or jib) and stowed it away. We got the boat ready so that we when we arrived at the marina, we could tie it up and leave. It was a bit after 8, when we came into the marina. We tied up and found that the party which had been planned in the grassy area by the marina, but had broken up, had left us some snacks and beers. I enjoyed a bag of chips and a beer. It was dark when I arrived at the marina that morning to carpool to Hilton Head and it was dark when I left the marina to head home.

Next Weekend with more wind (that’s me on the helm with Tito)

This was the first race since the St. Paddy’s Day race on March 14! While I’ve been sailing, all the other races and regattas had been cancelled due to Covid. The next Saturday was the Wassaw Cup, in which our crew wasn’t able to sail, so I sailed on another boat, with high winds, we were blown away. There’s one more race, at the end of the month, before I move to the mountains.

Boats gathering at the start of the Wassaw Cup

Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church

September 6, 2020

Matthew 18:15-20

Also, it seems I wasn’t the only one to come down hard on gossip this week. Even the Pope joined the chorus in his Sunday address. Click here for the AP article.

At the Beginning of Worship:

Technology has brought a lot of changes to our world, good and bad. On the positive side, it allows us to continue holding worship services during a pandemic, something that wasn’t available during the 1918 pandemic. But it also means everything is now more public, out in the open. Even things we might have hoped to do privately gets posted across social media for the world to see.

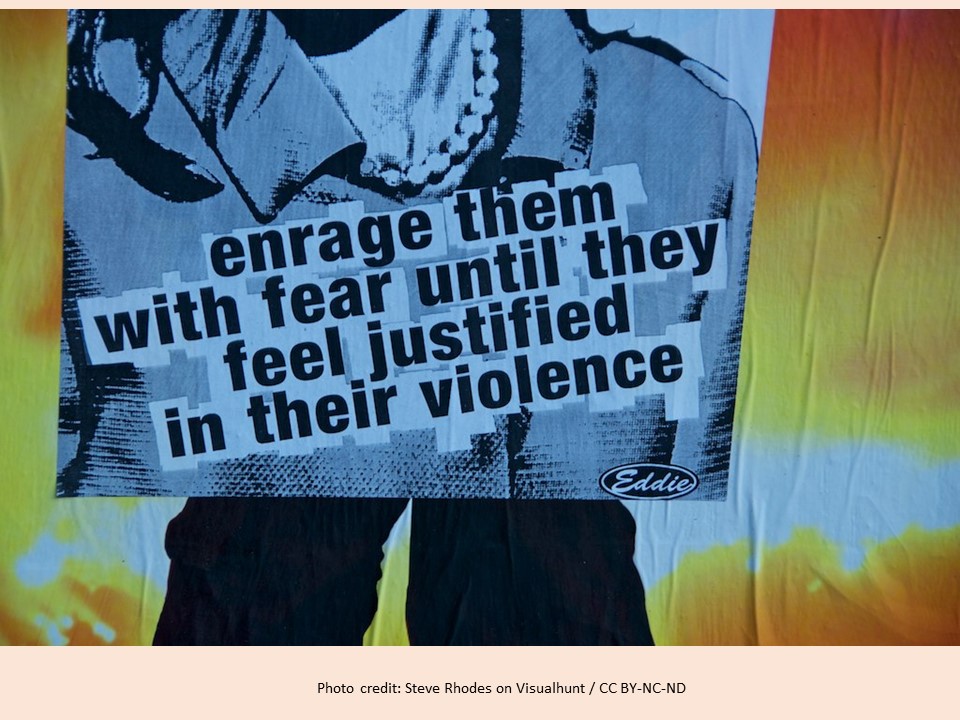

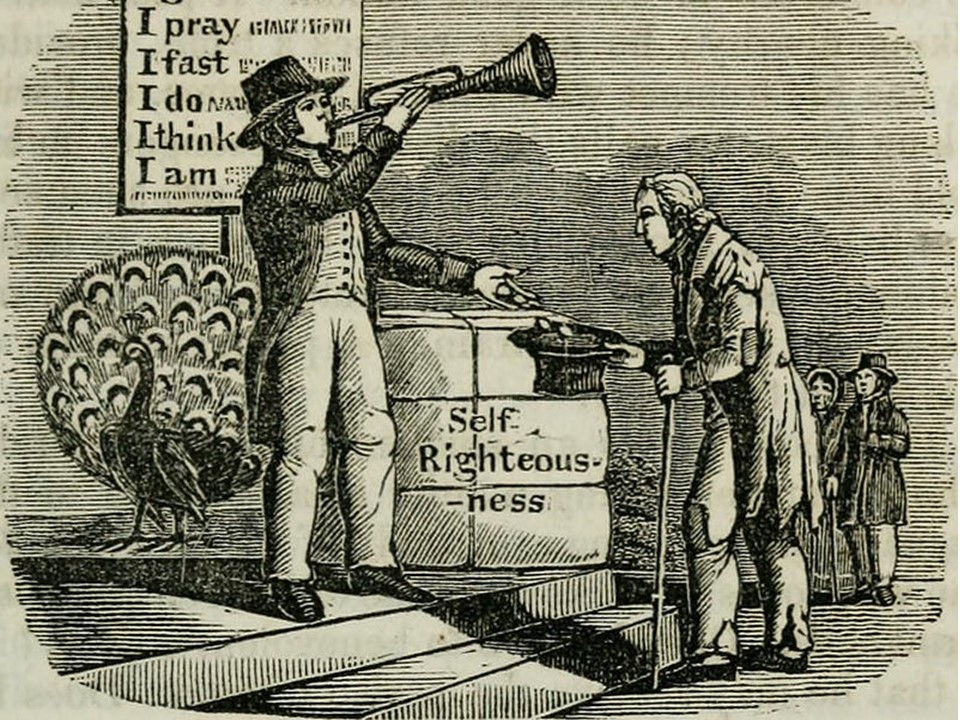

The downside of technology includes social media being filled with folks ready to attack anyone who might not agree with them. We’ve always had such people, but they used to easy to avoid. It’s amazing how people will attack others publicly, be it their food choices, their politics, or their use of grammar. Those who engaged in this manner think they’re doing something righteous when they blast an opponent. They think they look good and have power.

But is this how a Christian should act? Not according to the Scripture text we’re examining today. In fact, even when someone else is in the wrong, we need to go the extra mile to protect their identity, to show love, and to act with humility.

After the Scripture:

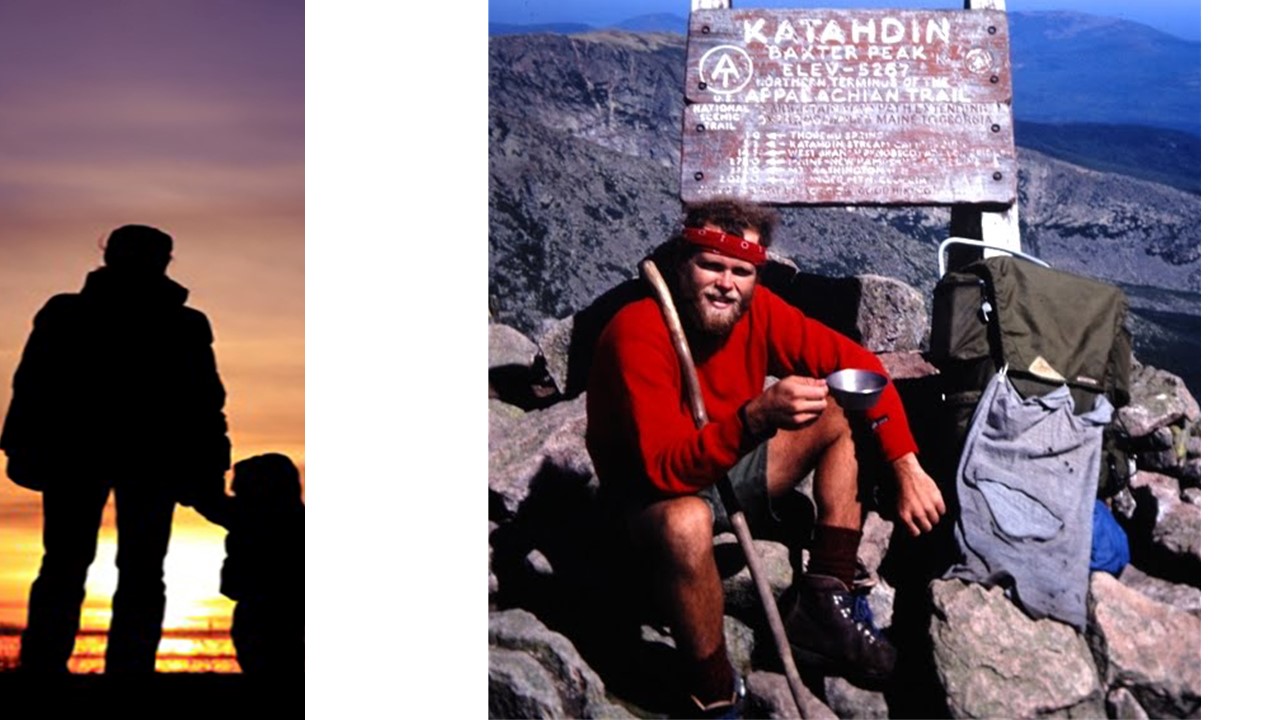

I always admire those folks who can take bucket of rust and, with hard work, restore the car to where it looks like it just rolled off the assembly lane. It takes time, patience, expertise, and a willingness to get one’s hands dirty. But what beauty can come out of such efforts.

Today’s sermon is about restoration. Not of cars, but of people. As Christians, we are not only to be about making ourselves betters, but also others.

Our passage from the 18th Chapter of Matthew speaks of correcting the sins of our brothers and sisters in the faith. Let me warn you, this is an easy passage to abuse. If we’re to be correcting sin, we need to first remember we’re all sinners. Second, we are dishonest if we only correct those sins we find most grievous or only the sins committed by those we dislike, while ignoring the sins of those we like. Remember, Jesus said something about us getting the log out our eyes before removing a speck from someone else’s.[1]

Pointing out the sins of others is something few of us want to do. That’s probably good. In the book The Peacemaker, which is mostly based on this passage, Ken Sande suggests those eager to go out and correct others are probably not the ones needing to perform such tasks.[2] The person who sets out to correct another needs to be humble and desiring both to restore the other person back into a relationship with Christ as well as to keep the publicity down. We’re not to try to make ourselves look better while making others look bad. That’s not Christ-like.

Like restoring an automobile, restoring relationships is hard work. It requires wisdom, love, gratitude, and humility. Without such gifts, one is liable to make a mess of things, just as having the wrong tools could ruin a car’s restoration. Without humility, we can make a mess of a relationship.

Now look at this passage. It starts with a difficult verse. Verse 15 is generally translated “if your brother sins against you…” The New Revised Standard Version translates it more to the intent of the original when it says if “another member of the church sins against you.” Matthew uses the word brother to imply all who are a part of the Christian fellowship, not just siblings or just men. The question that arises is whether we have the right to go correct others in sin.

If you take this passage as translated, the text implies that you go talk only to those who sin against you. Yet, almost all translations will have a footnote here, informing us that many of the older text omit the “against you.”[3] In such cases, it sounds as if we have a license to go correcting anyone who is in violation of God’s law. Since we’re all sinful at one point or another, the field is ripe for a harvest.

I’m going to do something maybe a little unorthodox and take both positions. If your brother or sister in the faith does something wrong against you, you are supposed to go to him or her. In other words, the harmed or the innocence party is supposed to make the effort to reconcile. Image that! My tendency, and this is probably true for most of us, is to avoid people who harm me, but that’s not what we’re being told here. And the object of the visit is not to beat up the offending party, but to restore them. We can also look at this verse from the angle of church discipline. Taking this verse to read: “If your brother does something wrong, go and have it out with him alone,” as the New Jerusalem Bible translates it, we’re told to confront those whose sins are so bad that they are harming the church of giving God a black eye.

Regardless of whether you think this passage applies only to sins committed personally against you as an individual or to sins in general, we’re not given a license to become intolerant moral police officers. Look at the context of this teaching. Right before here, in verses 10-14, Jesus gives the Parable of the Lost Sheep. The focus there, as in this passage, isn’t confrontation. It’s reconciliation, bringing the lost back into the fold. Then he follows this passage with the Parable of the Unforgiving Servant. Remember that passage is about judgment upon those who act harshly and are judgmental toward others. Having these two passages as bookends reminds us that Jesus is primarily interested in restoration of the sinner and that if we’re involved in bringing about such restoration, we’re to be humble and gracious.

We need to ask ourselves if the offense is great enough to risk ruining a relationship. Sometimes, having a little thicker skin will do wonders and further the peace.

If, however, the situation requires action, we’re to go to the other person and confront them face to face; we’re not to be talking about it to others, starting up the gossip mill. Today, thanks to social media, starting a rumor is easier than ever. But before we announce to the world the wrong someone has done, we’re to go talk to them. We’re to listen to what they say, for they may have a different interpretation or understanding.

Listening is important. We might have missed understood. Furthermore, if Jesus were teaching today, I think he’d insist that we listen and gather the facts before we march off into a crusade. As for social media, he would probably suggest that before we share something online, we make sure what we say is supported by facts and are not just emotional responses that demonstrate our own confirmation bias.[4]

After having confronted the person face to face, if they are not willing to work things out or if they are going to continue sinful activities, we’re still not to start gossiping. We’re to maintain confidentiality as we attempt to come to an understanding with two or three others, who are trusted and will also keep confidentiality. In Sande’s book, he recommends that if we’re in a conflict with someone else, we tell them at the end of that first meeting that we’re going to seek the council of others—for if they know they’re in the wrong they may be willing to go ahead and work things out with us.

These two or three witnesses serve two functions. First, they are observers. Judgment in Scripture always required two witnesses.[5] In this case, they are there to make sure that things are fair. They might listen and think we’re the one that is in the wrong and, in that case, we have to be willing to accept their advice.

After this second visit, if we still don’t resolve the problem, then we can take our complaint back to the church. In keeping with the process, this doesn’t mean that we stand up during joys and concerns and broadcast the complaint to everyone. Instead, we take it to the leadership, to those in charge, and let them be the judge. Only after this intervention fails, does the church have a right to exclude the offending party from the community of faith. Matthew says that then they’ll be like “pagans and tax collectors.”

What are our responsible toward correcting a member of the community who sins, remembering that we all sin? This was debated heatedly during the Reformation. John Calvin, one of the founders of our branch of Christendom, supported Church discipline for three reasons.[6] First, was to honor God. The church should act against those who are in open revolt against God. But Calvin did not suggest we start inquisitions. He never argued for a “pure church” because he believed that was impossible. Church discipline was taken only against those who openly refused to stop and repent of their blasphemous activities. The second aim was to keep the good within the church from being corrupted, and the third aim was to bring the guilty party into repentance.[7] Discipline was always carried out in hopes of restoring the contrite into the fellowship of the church. In other words, discipline was done pastorally out of concern for the accused soul.

When we take these verses out of their setting, they sound harsh. After all, Christ gives those of us in the community the power to banish someone from our midst.[8] He even tells us that decisions we make here have eternal ramifications. But our purpose isn’t to be the enforcer; instead our goal is to restore the sinner. And if we’re going to be convincing, we got to remember that we’re all sinners, which means we better be humble in any endeavor we undertake.[9] We don’t try to correct others as a way to prove our rightness, but out of love and concern. Like restoring a car, it’s hard work. Amen.

[1] Matthew 7:5.

[2] Ken Sande, The Peacemaker: A Biblical Guide to Resolving Personal Conflict (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2004).

[3] There is debate over the inclusion of this phrase. See Bruce Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (United Bible Society, 1985), 45 and Douglas R. A. Hare, Matthew: Interpretation (Louisville: John Knox Press, 1992), 213. Robert Gundry argues for its inclusion in Matthew: A Commentary on his Literary and Theological Art (Grand Rapids: Eerdman, 1982), 367; while Frederick Dale Bruner omits the phrase. See The Churchbook: Matthew 13-28 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004), 225.

[4] Confirmation bias is agreeing with something because it “fits” our world view without verification. In other words, we decide something is right because it fits our existing beliefs.

[5] Deuteronomy 19:15.

[6] Although Calvin supported and participated in church discipline, unlike some Reformers such as John Knox, Calvin did not see discipline as one of the marks of a “true church.” To him the marks of a true church was the proclamation of the gospel and the rightful administration of the sacraments. For a discussion of Calvin and discipline, see Charles Partee, The Theology of John Calvin (Louisville: W/JKP, 2008), 270-271.

[7] The three purposes of discipline of John Calvin are in his Institutes of the Christian Religion, IV.12.5..

[8] While this is seen in this passage (Matthew 18:18), it also appears in Matthew 16:19.

[9] Heimlich Bullinger, another reformer and author of the Second Helvetic Confession tempers his talk on discipline with a reminder that Jesus said not to pull the weeds up because you risk pulling up the wheat. See Presbyterian Church (USA), Book of Confession. 5:165.

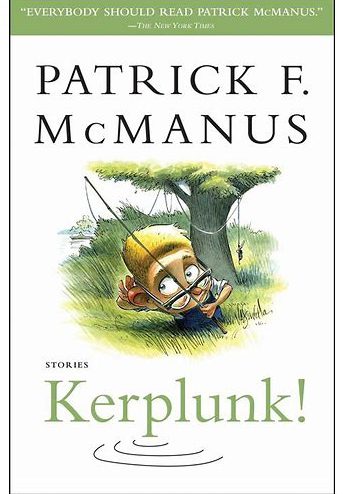

Jesse Cole, Find Your Yellow Tux: How to be Successful by Standing Out (Lioncrest Publishing, 2018), 303 pages, some photos.

Jesse Cole, Find Your Yellow Tux: How to be Successful by Standing Out (Lioncrest Publishing, 2018), 303 pages, some photos.

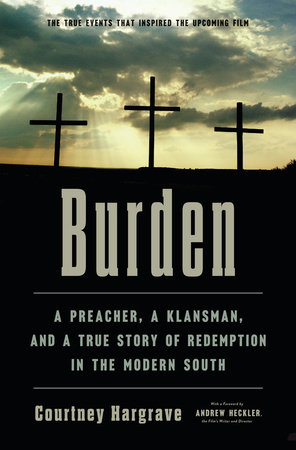

The Back Story: One of the most amazing things I’ve seen while living in the Savannah area is the development of a summer league baseball team for college players, the Savannah Bananas. Before the Bananas arrived, there had been a Single-A minor league team, the Savannah Sand Gnats. I went to one of their games the first full summer I was here with my staff. We pretty much had a whole section of the stands to ourselves. It is hard to think that I cheered for any Sand Gnat. As is often said around here, that nasty bug and the humidity are what keeps house prices affordable along the Georgia Coast. The Sand Gnats tried to get the city to build them a new stadium (Grayson Stadium is old but classic—even Babe Ruth played there). Failing to blackmail the community into a new stadium, they moved to Columbia, South Carolina, but sadly left the gnats behind. It wasn’t looking good for baseball in Savannah until this young man from Gastonia, NC comes along with some crazy ideas. He creates a ball team of college players and tops it all off with entertainment and fifteen buck tickets that include all you can eat burgers and hotdogs. It’s a great deal and fun. The first summer, about forty people from our church attended a game. I took a photo of a dude wearing a yellow tux and posted it to Facebook, asking what would happen if I wore a yellow tux in the pulpit. One of my elders responded (jokingly, I think) that they might have to establish a new Pastor Nominating Committee. I still think it would have been a fun idea.

Jesse Cole at a ballgame in 2016

My review: The dude I saw in at that baseball game back in 2016 was the author of this book in which he lays out his ideas about business and life. It’s all about having fun and doing what you can to stand out in the world. Cole’s idea is to do crazy things to draw attention and to build a fan following. It works. While the Sand Gnats never sold out, the Savannah Bananas sold out the stadium their first three years. This book is part business manual and part memoir. We learn about Cole’s life, which is almost like a novel (I know of several novels where someone hoped to play professional ball and throws their arm out in college). Cole finds a way to stay with the game, first in Gastonia, N.C. and now in Savannah. The book draws on many others who gave Cole inspiration: Walt Disney, P. T. Barnum, Mike Veeck, Richard Branson, the movie “Jerry Maguire” among others. Cole is not only an avid reader; he is able to put what he learns into action. He also encourages those who work with him to read and to produce ideas. Some of his ideas are a new spin on an old idea. Cole uses an old fashion “idea box.” But what he does with those ideas are unique. “Brainstorming” is called Ideapaloozas. Cole points out the lack of excitement with “professionalism” and encourages everyone to be crazy, doing the opposite of normal. He insists that their only focus is on their fans. While Cole never mentions investments, his idea of doing the opposite of what everyone else is doing sounds like the contrarian investment strategy (See Dreman, Contrarian Investment Strategies). His goal is to be successful while having fun and putting his fans first (Fans First Entertainment is the name of Cole’s business).

When I started reading this book, I thought it should be read by everyone in leadership at Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church. By the time I was done with it, I thought it should be read by everyone. I recommend you read it and start having fun while you find success by helping others.

Jeff Garrison

Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church

August 30, 2020

Matthew 16:21-26

Click here to watch the service. The sermon begins at 18 minutes if you want to fast-forward.

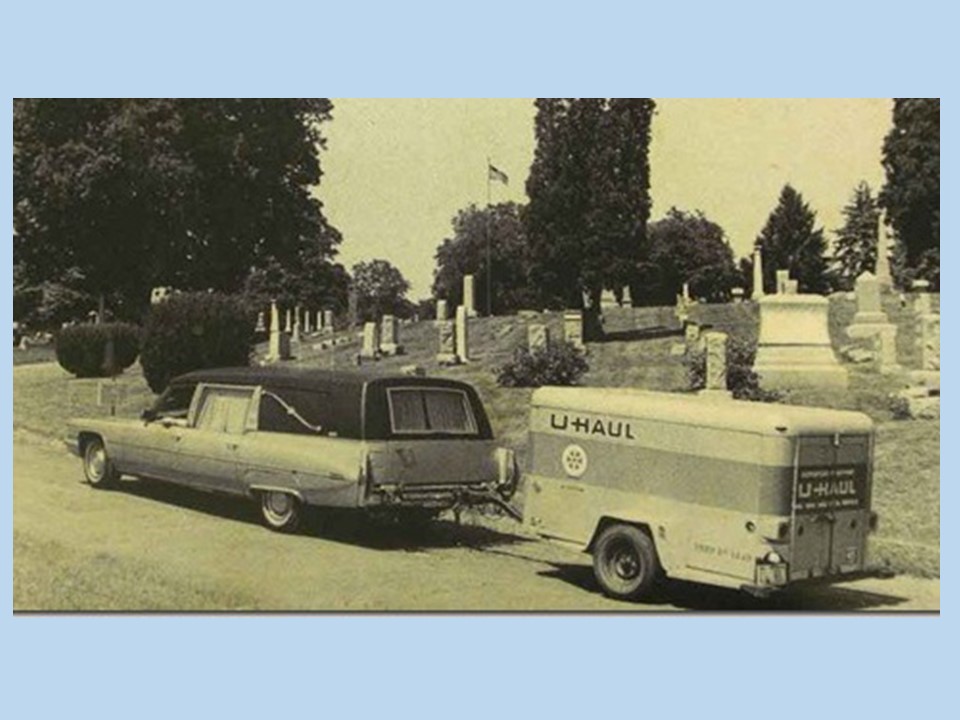

Beginning of Worship: I saw a meme the other day. A man at a bar ordered a Corona and two hurricanes. “That’d be 20.20,” the bartender said. It’s not been a good year so far. It seems like we’ve all been carrying a cross over the past eight months. But is this what Jesus means when he says we are to pick up our cross and follow him?

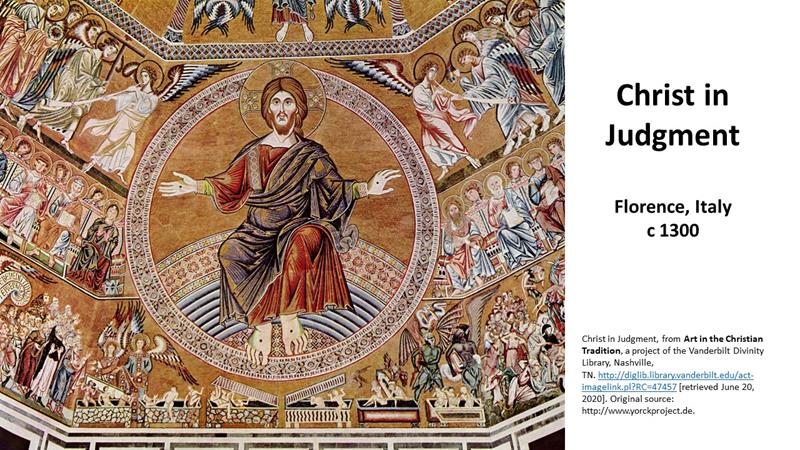

The cross is a symbol we see everywhere. We have several in our sanctuary. We wear it as jewelry. It populates cemeteries and are often placed beside the road where there has been a fatal accident. But what does it means when Jesus tells us to pick up the cross? That’s today’s topic.

This is our second Sunday in the 16th Chapter of Matthew. If you remember, last week, Peter nails it. He confesses Jesus to be the Messiah. Today, he doesn’t look so good. He can’t accept Jesus’ plan involving the cross. Last week, Peter was praised. This week, he’s called Satan. There’s good news here because our lives are similar. We can do good and great things and we can do rotten things. Aren’t you glad there’s grace?

Jesus does something radical and he invites us to follow him, but it’s a costly invitation. Jesus demands our very lives. For those of us who follow Jesus, the cross becomes our sign of God’s power as Paul eloquently states in First Corinthians, but to others it’s foolishness.[1] But as a sign, the cross is not easily understood.

###

After the Scripture Reading: What does it mean to pick up our cross and follow Jesus? Maybe a better way to ask this question is what does it mean to be a follower of Jesus Christ? We have to be careful that we don’t cheapen the bearing of our cross in an attempt to explain our trials. Carrying the cross isn’t just enduring a bad time, like 2020. Picking up our cross and following Christ has life changing implications. We admit we’re not in control. It’s no longer about us and what we want and what we think we need. Instead, it’s all about the man up ahead, the one we are following.

Think about the theology of the cross in light of two seeming contradictions in scripture: Jesus’ call for us to pick up our cross and proclaims that he’s come to set us free.[2]

In Jesus’ day, no one thought of the cross as a sign of freedom. In fact, a cross was viewed in just the opposite. It was a sign of torture, a reminder of the imperial power of Rome that subjected a huge portion of the population to slavery. In Rome, if a slave rebelled, the cross was the normal method of execution. The cross was a tool the Romans used to cement their control. When Jesus tells the disciples to pick up their cross and follow, they may have had second thoughts.

This particular passage is recounted in all three of the synoptic gospels—which tells us something about the impression it made on the disciples.[3] Yes, we know Peter doesn’t like the idea of Jesus dying, but that was all before Jesus issues this command. None of the gospels give us an idea of how the disciples and the crowd responded to Jesus’ call at this point. Such an omission is a part of the plan, I believe, for it allows us to respond to Jesus’ call in our own ways. This morning, we’re wrestling with what it means to pick up our cross. First, I am going to discuss some mistaken ways this call is interpreted: I’ll label these three as triumphant militarism, naive pacifism, and sentimentalism. Then I will offer ideas on how we are to be a servant of Jesus Christ and faithfully answer his call.

Peter’s idea of picking up the cross falls into my triumphant militaristic category. Remember, he’s the disciple who, at Jesus’ arrest, pulls out a sword and slashes the ear off of one of the men.[4] I imagine Peter, a fisherman whose muscles were well defined from working the nets, as a strong man. At this stage of his Christian walk, he’s a Rambo type character, ready to pull up the cross and use it as a club to pound his foes. Peter and the other disciples are ready for Jesus to set up a worldly kingdom. Peter wants Jesus to be King so he can be an advisor, right next to Jesus’ throne, the second in command.

When Jesus started talking about this suffering stuff, Peter gets nervous and decides he’d better try to steer his leader in a different direction. “Hey Jesus,” Peter remarks, “let’s rethink this part about dying.” But Jesus’ way wins out. The cross is not to be used by us as a weapon, nor does it give us any protection other than being a symbol of what Jesus has done for us.

If triumphant militarism is one extreme rejected by Jesus, so is the other extreme, which I label naive pacifism. I chose the term naive because pacifism for many Christians is an appropriate response. But when the path is naively chosen, we forget that we’re called to resist evil, to deny evil power in the world and instead we become a sacrificial pawn. Just as we should not use the cross as a weapon, it’s not to be used as a white flag of surrender, either. Jesus picked up his cross and carried it to Calvary in order to offer his life for sins you and I have committed. Jesus died for our sins so that we don’t need to die for them, nor should we be expected to die for the sins of others. But this doesn’t mean there’s not work for us to do.

If we’re not to be militants or pacifists, we might be led to think the proper understanding—the middle way of understanding Jesus’ call—is sentimentalism. Sadly, this is the way many people look at the cross. We clean up its horrific image and use it as jewelry and decor on our cars. But such an understanding of the cross—if it goes no deeper—misses the point. It can even become a political statement or a superstition, which is idolatry. If the cross is only seen for its sentimental value—we’ve cheapened Jesus’ call.

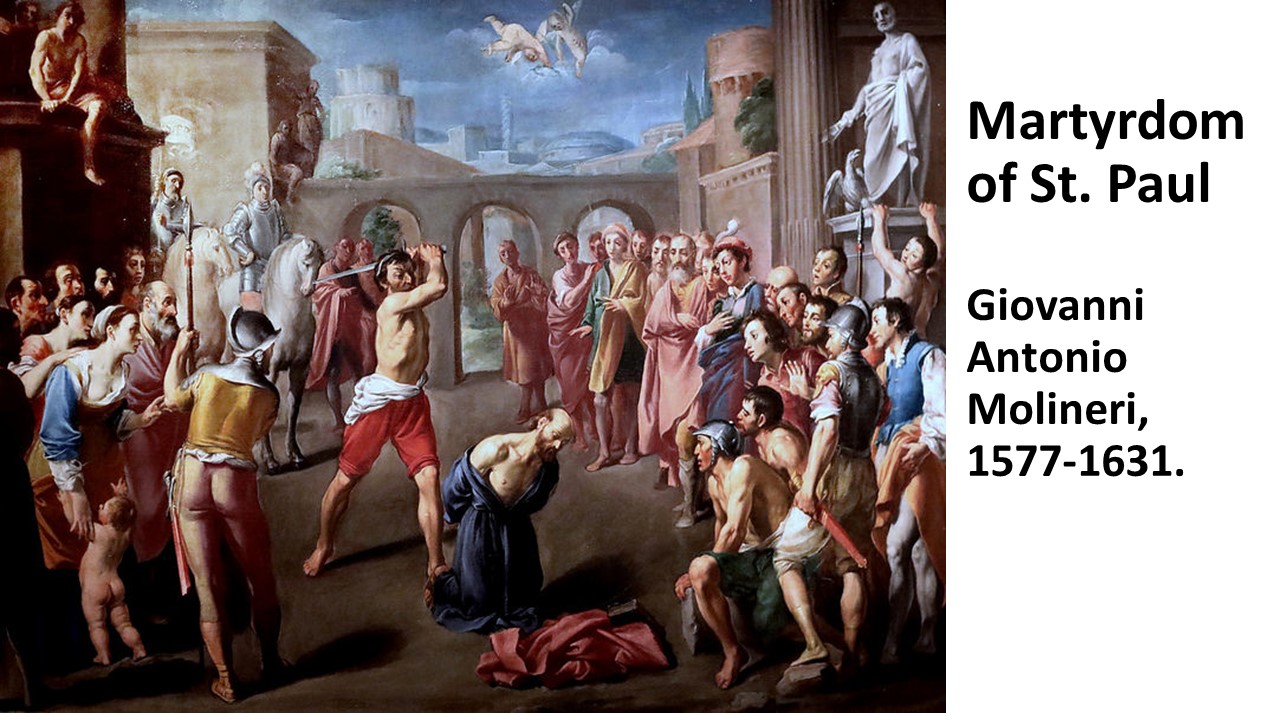

I don’t know if I can give an understanding of what picking up one’s cross should mean to us all. Certainly, I think it means more than having a piece of jewelry. For a few people, it may mean martyrdom—as it did for many of the disciples. But Jesus certainly didn’t expect all his followers to be crucified. Secondly, martyrdom is not the highest virtue. Instead of martyr, the virtue we strive for is faithfulness. Yet, we learn from Jesus, if we love our life we will lose it. Paul expands this thought when he speaks of our need to put to death the desires of the flesh and to live for Christ.[5]

By calling us to pick up our cross, Christ informs us that we’re not in charge of our Christian journey. We must be willing to follow him. Our calling isn’t about our needs or our desires, but about Jesus’ desire for us and for our lives. As Christians, we all have a calling that is linked to our vocations. Since we live our Christian life throughout the week, and we all have different occupations and trades, we each have to determine how we can best be true to our Savior. I can’t give a single definition of what picking up our cross will mean for everyone, just as Matthew didn’t tell us of the disciples response to this call.

As a seminary student, when I was a camp director in Idaho, we had each of the campers carry a live-size cross during a hike. Afterwards, around a campfire, we debriefed. Some told how difficult it was to physically carry the cross—toting the awkward beams and of the splinters. Others spoke about how they were uncomfortable to be out front of the rest of the campers, with everyone following and looking at them. Others had even more difficulty watching their fellow campers struggle. These wanted to show compassion by taking the burden of their friends.

These responses from the campers provide an insight into what the cross means and maybe an idea of how we pick up our crosses. When Jesus took up his cross, he was taking on the burdens of the world. He didn’t take the cross on his own behalf, but on our behalf. It wasn’t someone who lived a comfortable life that brought salvation to the world; it was someone who shared in the suffering of the whole world. We must understand that Jesus’ death on the cross is sufficient for our sins and the sins of the world.[6]

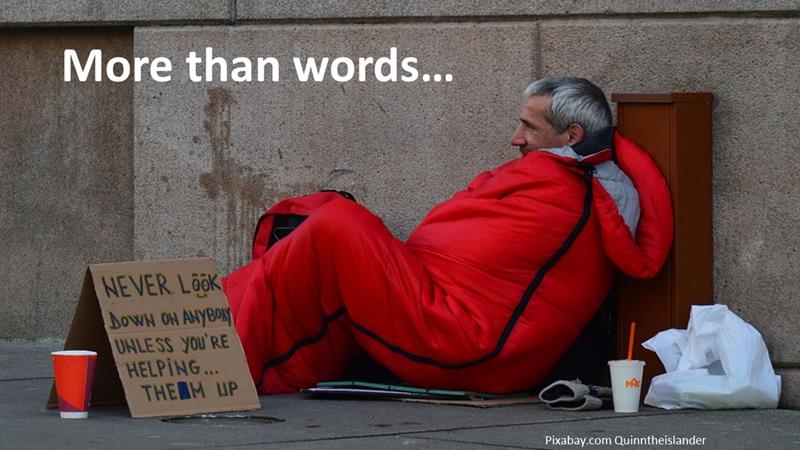

The penalty for sin—death—has been paid in full and none of us is being called to make another deposit—we’re not being called to save the world.[7] By picking up the cross, Jesus shows his willingness to share in our pains and sorrows. And he calls us, his disciples, to share in the pain of others. The campers who expressed compassion for the one carrying the cross understood, at least partly, what is means to be indebted to someone for taking on our burdens and for us to be ready to have compassion for others who are in pain. One meaning of picking up our cross is for us to be willing to stand beside others in need—whatever form that need might take. Jesus takes our burdens, he shoulders our cross, and the only way we can have a glimpse of what he feels is to feel the pain and burdens of others. So maybe our crosses have to do with how we show compassion.

I think our vicariously sharing in the pain of others also helps us to understand the proverb Jesus cites at the end of our passage. Jesus reminds us that whoever wants to save their lives will lose them and whoever loses their lives for his sake will find them. This is one of those great reversal statements of Jesus, but notice Jesus doesn’t call us to lose our lives in the lives of others. Rather, he calls us to place himself first in our lives—to put our total trust in him. Our call to discipleship is not to place some other than Jesus first (despite what politicians—many of whom have a messiah-complex, might hope for). Nor is our call to place ourselves first. It’s a call to follow Jesus and put our total trust in him. It means we must obey the first commandment: to have no god other than the one true God. It means to take seriously the great commandment: to love God—the God revealed in Jesus Christ—with all our hearts and souls and minds and strength.

If we are grounded in our love for God as revealed in Jesus Christ, we will be able to fearlessly pick up our crosses, whatever form it may take, when Jesus calls. This means following Jesus even if it means losing our friends or being alienated from our families. This means following Jesus even though we will be despised. And it means we must be willing to follow Jesus even if lose our lives. We follow Jesus, and only him. Jesus is all that matters. Amen.

©2020

[1] 1 Corinthians 1:18

[2] See John 8:32-36.

[3] Matthew 16”24-28, Mark 8:34-9:1 and Luke 9:23-27. In each of these gospels, this scene is followed by the Transfiguration. Only Mark has the previous story of Peter confessing Jesus to be the Messiah.

[4] John 18:10.

[5] Romans 8:13.

[6] See Hebrews 10:1-18.

[7] 1 Corinthians 15:56.

Things have been busy at my house as we are now showing it and trying to begin packing for our move to Virginia… But the busyness hasn’t kept me from sailing, as I crewed a boat up to Hilton Head on Friday and then on Saturday, we raced back to Skidaway (I’ll have to do a post on the long race with little wind, because we too first place in our class). I finished this book when in Virginia a few weeks ago.

Robert A. Caro, The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power (New York: Alfred Knopf, 2012), 712 pages including notes and sources and 32 inserted pages of black and white photos.

Robert A. Caro, The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power (New York: Alfred Knopf, 2012), 712 pages including notes and sources and 32 inserted pages of black and white photos.

This is the fourth volume in Caro’s massive study on Lyndon Johnson, and the third I’ve read. In this book, Caro begins with the run up to the 1960 Democrat Convention. It was assumed that 1960 would be the year Johnson would run for the President. With his leadership in the Senate, Johnson was a powerful man. But he kept giving off mixed signals as to his intentions to run and once he stepped into the race, he bet that no candidate could achieve a majority of the votes during the first round at the convention. In that case, many would switch to Johnson and he could capture the nomination. Johnson was too late for Kennedy had wrapped up a majority of delegates. As Caro has done in the other volumes, he provides mini-biographies of key players in the story including both John and Robert Kennedy. After Kennedy was selected as the candidate, he chose Johnson as his Vice President candidate. Even this wasn’t without drama as there was a question whether or not Johnson would accept the position, as he’d be leaving the second most powerful position in the country with his leadership of the Senate. But Johnson, who wanted to be President since his childhood, accepts the position realizing he’s only a heartbeat away from the Oval Office. Caro, through extensive work, debunks the theory (that has been popularized by Robert Kennedy and his friends), that Kennedy’s invitation to Johnson was just a nice gesture and one that they assumed Johnson would decline. Robert Kennedy and LBJ would continue to have a running feud the rest of their lives. Caro makes a convincing case that without Johnson, who wasn’t as well liked in more liberal areas in the north, Kennedy would have never been able to win the presidency in 1960.

After the election, Johnson found himself sidelined. His feud with Robert Kennedy continued to grow. His advice on how to handle legislation in the Senate (something he understood) was ignored. As a result, Kennedy wasn’t able to achieve most of his agenda. Johnson, who was more hawkish, was even kept out of key meetings such as with the Cuban Missile Crisis. Compounding Johnson’s problems was the investigation into some of his supporters, especially Bobby Baker. This had the ability to cripple Johnson and perhaps even keep him off the ticket in 1964. Interestingly, Caro tells the story in a suspenseful manner as the hearings on Bobby Baker was running in Washington DC as the motorcade in which Kennedy was shot was driving through Dallas.

Upon the death of Kennedy, Johnson changed. He quickly assumed power. He knew what needed to be done to send the right signals to the rest of the world in to halt any mischief that the Soviets or the Cubans might stir up. Caro, who in previous volumes have been critical of Johnson and points out his flaws, has high praise of how he conducted himself through the end of 1963 and into 1964. Johnson was able to achieve Kennedy’s goal of a tax cut along with Civil Rights legislation. His handling of the segregationist Harry Byrd was masterful, as he presented a lean budget to win Byrd while working to keep him from blocking civil rights legislation. He was able to keep most of Kennedy’s staff and win their loyalty. While Johnson is often remembered for being mired down in Vietnam, Caro praises his ability to guide the country through this difficult time. He also put his own stamp on the Presidency by showing foreign leaders a good time at his ranch in Texas. In the spring of 1964, Johnson had the highest Presidential poll rating of any President.

Like Caro’s other books, The Passage of Power is a masterful volume that captures the complexity of the first President that I remember. I hope Caro will soon come out with his 5th volume, that looks at Johnson’s 1964 victory against Barry Goldwater and how his Presidency collapsed with the failures in Vietnam, leading up to his refusal to run for a second term in 1968. If you’re interested in history or in the complexity of powerful leaders, I recommend this book.

Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church

Matthew 16:13-20

August 23, 2020

Click here for the worship service. Advance to 15:30 to begin watching the scripture and the sermon.

At the Beginning of Worship

What does it take for us to be true to our calling as Christians? What are the most important activities that makes us a church? There are two, which are outlined in the second half of the 16th chapter of Matthew’s gospel: confessing Jesus as the Messiah and following Jesus, even to the cross. At times like this when society is semi-closed due to the pandemic, these two essentials remain. Are we still doing them? Today, is my first sermon from this part of Matthew 16, and we’ll look at the first requirement, confessing Jesus as the Messiah.

The Message (after reading Matthew 16:13-20)

After a long illness, a woman died and arrived at the Gates of Heaven. “How do I get in?” she asked.

“You have to spell a word”, Saint Peter told her.

“Which word?”

“Love.”

“L-O-V-E,” the woman spelled out and the gate swung open and she entered.

About three years later, Saint Peter needed a day off and asked the woman to watch the Gates of Heaven for him. Guarding the gate, she was shocked when her husband arrived. “How have you been,” she asked.

“Oh, I’ve been doing pretty well since you died,” he said. “I married the beautiful young nurse who took care of you while you were ill. And then I won the lottery. I sold the little house we lived in and bought a big mansion. My wife and I traveled all around the world. We were on vacation and I went water skiing today. I fell, the ski hit my head, and here I am. How do I get in?”

“You just have to spell a word”, she said.

“What’s the word?” he asked.

“Czechoslovakia.”

You may be wondering what this has to do with our text today. Well, there’s a weak link. You see, the idea of Peter being heaven’s gatekeeper comes from this passage, where he’s presented the keys and given the power to open doors. These jokes have been told for a long time. One source suggests that St. Peter at the gate jokes have been around since the 14th century and were originally used to tempt monks to break their vows of silence.[1] Although their context comes from our morning passage in Matthew, we have to realize that the jokes have little relevance into how one is admitted into heaven.

Let me tell another. A devout Presbyterian woman arrived at the Pearly Gate. Peter asked her why she should be admitted and she acknowledged that she really didn’t deserve being let into heaven, but that God was gracious and had ordained her for salvation in Jesus Christ. She staked her future on that promise. Peter nodded affirming. As the swung the gate open, the woman brought out a casserole. “Just in case grace wasn’t enough,” she said, offering it to Peter.” We like to hedge our bets, don’t we?

Now, let me assure you, getting into heaven isn’t what this passage is about. This passage is about who is Jesus. Jesus and the disciples have been together for sometime at this point. They’ve travelled together, teaching and healing and taking care of people and proclaiming the kingdom. Its only now, after they’ve extensively invested themselves into this man named Jesus, that he forces them to deal with his identity.

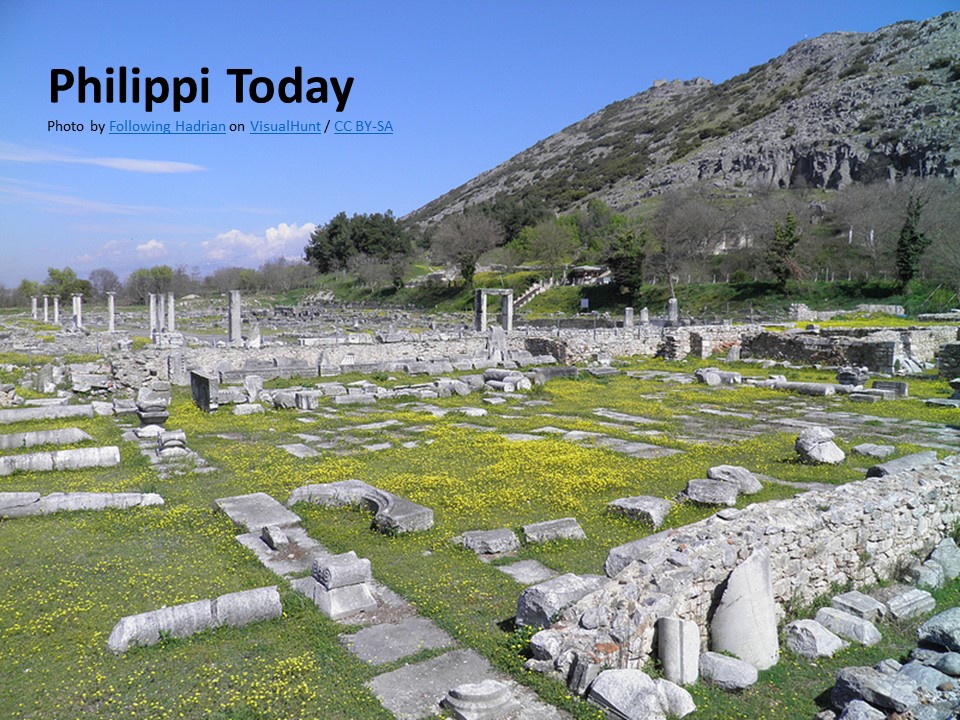

The setting for today’s passage is in the region of Caesarea Philippi. You are probably wondering what that has to do with anything. It’s important! This city was on Israel’s northwestern border. Before Jesus’ birth, Herod the Great built a magnificent marble temple there in honor of Caesar. His son, Philip, enlarged the city and renamed it Caesarea in honor of Caesar Augustus. But there were other Caesareas around, such as the one over on the coast. Philip, a politician, liked to see his name in print, so the city became known as Caesarea Philippi. It honored both Caesar and Philip.[2] This is the important part. It’s here, in this city devoted to the worship of the Emperor, that Jesus asks the disciple who they think he is. Deep down, there is a political statement being made here. If Caesar is Lord, then who is Jesus? Or vice versa. It’s interesting, that while Jesus took the disciples into pagan lands, from what we know, he never said anything derogatory about the paganism. We should learn from him. But by focusing on his identity and mission at a place where Caesar was worshipped as God on earth, Jesus challenges earthly powers.[3]

Jesus first asks the disciples what people are saying about him. “Oh, some people think you’re John the Baptist, raised from the grave, or Elijah, or Jeremiah, or one of the other prophets.” This first question was a teaser, for then Jesus goes to the heart of the matter. He asks a question we must all answer, “But who do you say that I am?”

Ultimately, it all comes down to this question, doesn’t it? I can see why people believed Jesus to be a prophet, for he had done great things. Most people like Jesus, even those who are outside the church. He’s known as a good and kind man who was a good teacher. I recently had someone tell me that she doesn’t consider herself a Christian anymore, but she loves Jesus. I wasn’t sure what to make of that. The book They Like Jesus But Not the Church, points out how most people in our country like Jesus and how the church is often a barrier from people getting to know Jesus better. That hurts, but some churches are so overzealous with a desire to save (which is the Spirit’s work, not ours), that all they do is to encourage people to accept Jesus when people don’t even know who they’re talking about. Jesus has invested a significant portion of his time with the disciples before he hits them with this question, “Who do you say that I am?” Likewise, we need to invest time discovering who Jesus is and talking to others about who he is before we try to encourage them to join up and become a follower of the Savior. We plant the seed, God brings about the harvest.

When Jesus asks the disciples who they say he is, Peter responds: “You are the Messiah, the Son of the Living God.” Peter nails it. This is no weak response. There are no qualifying phrases. He doesn’t say, I think you’re the Messiah,” or “You appear to be the Messiah.” Peter is direct and his confession is the foundation of the church. “Jesus is the Messiah!” Peter is staking out what he believes, even though as we will see next week, he doesn’t really understand the implications of what he has said. But that’s okay, for as Jesus informs us, Peter wasn’t speaking on his own; his confession is coming from God. Then Jesus called Peter the son of Jonah, which is an interesting and paradoxical reference. First, Peter caught fish, a big fish caught Jonah. In addition, Jonah isn’t exactly a model for he ran from God, just as Peter ran after Jesus’ arrest. Another and maybe a more important parallel is that Jonah was a prophet to Gentiles, and that’s the direction the church will take under Peter’s leadership.

Peter is important. Jesus says, “You are a rock and on this rock I will build MY church.” There has been plenty of controversy over this passage. The Roman Catholic Church sees it as the beginning of papal succession, that the rock refers to Peter as the pope. We Protestants question this idea. Yes, Peter plays an important role in the establishment of the church, but the church leadership throughout history isn’t from Peter as an individual, but is invested within the body of the church.[4]

More importantly than the rock concept is the emphasis that Jesus places on “my church.” It’s clear, the church doesn’t belong to Peter or to the disciples as a whole, nor does it belong to us. The church belongs to Jesus Christ. He’s the one who gives the church life and its power. Certainly, as a body we can do great things. We’ve even been given the keys to the kingdom![5] But our abilities aren’t due to who we are, but to whom we worship. Even death cannot stop the church, which is the meaning of the “gates of hell or Hades shall not prevail.” In Jesus’ day, Hades was a place for the dead, but death has no power which Jesus will demonstrate with the resurrection. The church is to have one focus: Jesus Christ. It’s his name we lift up in praise, it’s his example we lift up as a model for our lives, it’s his power we rely upon when we don’t have the strength to do what we need to be doing. We depend upon Jesus.

While we are totally dependent on Jesus, we are still valuable and endowed with responsibility. The church is given great power, including the power to loosen or bind sins, or the power to forgive sins and to withhold forgiveness.[6] That’s an awesome power. We should accept it with humble reverence for Jesus doesn’t give it for us to use for our sake or to abuse for our benefit, but for us to use to help others become more Christ-like.

Our passage ends with Jesus telling the disciples to keep a secret about his identity. We may find this strange. Wouldn’t Jesus want everyone to know? Certainly, when we get to the end of Matthew’s gospel, Jesus sends out the disciples to all nations with the command to baptize and to make more disciples.[7] That commandment, known as the Great Commission, is for all believers. But here, before the resurrection, we must guess as to why Jesus wants the disciples to keep this secret. Perhaps it is because he knows that they do not yet fully understand the implications of Peter’s confession. Maybe Jesus is afraid they’ll mix in their own incorrect ideas and political opinions and muddle the message.[8] We don’t know for sure why Jesus wants them to be quiet at this point, but certainly, after the resurrection, Jesus is forceful in his command that we go out into the world and share his love.

Now it’s back to us? Who do we say Jesus is? Our first goal, as a follower of this man from Galilee, is to understand him. As I pointed out earlier, Jesus didn’t spring this question on the disciples the first day they were together. The disciples have spent a significant amount of time with him, maybe nearly three years at this point. To be able to answer that question, we must pick up this book (the Bible) and read about him. We must study the gospels. We must take our questions to him in prayer. And as we come to know him more fully, we need to begin to question our lives and see where we fail to live to his standard, and to be honest to Jesus in prayer as we repent. And finally, as we learn more about him, we need to share our knowledge with others, so that they too may know him.

You know, in this time with things slowed down because of the pandemic, now is a perfect time to work on your relationship with Jesus. Read one (or all) of the gospels. Write down for yourself your questions and who you think Jesus is and what he means to you. Having such a foundation will help you articulate your faith when it’s important. It’s a good investment in your eternal future. After all, what are you going to say to St. Peter at the Pearly Gates? Being prepared is better than bringing along a casserole. Amen.

©2020

[1] In searching for jokes, I came across this sermon which had the jokes I’ve used (I’ve altered them a bit) along with the suggestion as for the jokes origin: http://geoffreythebold.blogspot.com/2005/09/fabled-pearly-gates-joke.html

[2] John Kutsko, “Caesarea Philippi,” Anchor Bible Dictionary Vol. 1 A-C, David Noel Freedman, editor (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 803.

[3] To learn more about the political reference here and why Caesarea Philippi matters, she Scott Hoezee’s take on this passage: https://cep.calvinseminary.edu/sermon-starters/proper-16a-2/?type=the_lectionary_gospel

[4] Bruner, 127-130 and 135-137 and Douglas Hare, Matthew: Interpretation, a commentary for preaching and teaching (Louisville: John Knox Press, 1993), 191. Bruner, in an in-depth discussion on Peter’s role later in his commentary quotes another commentator who tries to bridge the “hyper-Catholic” and “hyper-Protestant views of Peter and summarizes him as “a man with a unique role in salvation-history… his faith is the mans by which God brings a new people into being.” Bruner, 137.

[5] Although in this passage, Jesus refers to Peter as the one with the keys and the ability to bind and loosen, later in Matthew’s gospel he speaks of all the disciples (and the church) being given this power. See Matthew 18:18.

[6] Historically, the words “loosen” and “bind” have been understood in two ways. Doctrinally, they refer to the ability to loosen (or open) through teaching the way of Jesus and their binding is a warning of the consequences of not hearing and abiding in the word. Secondly, these words have a disciplinary meaning. The church has the right to bind disobedient believers, and to loosen the bindings of those who are repentant. Bruner, 132.

[7] Matthew 28:19.

[8] Burner, 137-138, makes this point.

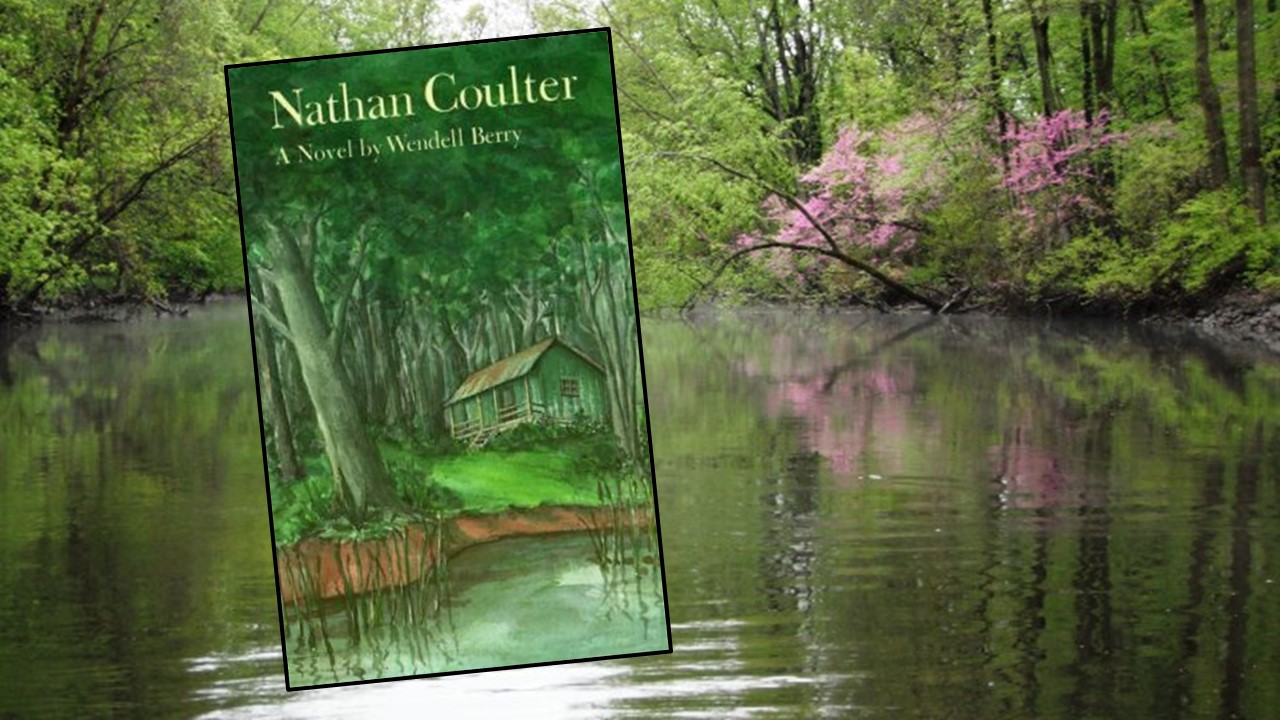

David Lee, Mine Tailings (Boulder, UT: Five Sisters Press, 2019), 79 pages.

David Lee, Mine Tailings (Boulder, UT: Five Sisters Press, 2019), 79 pages.

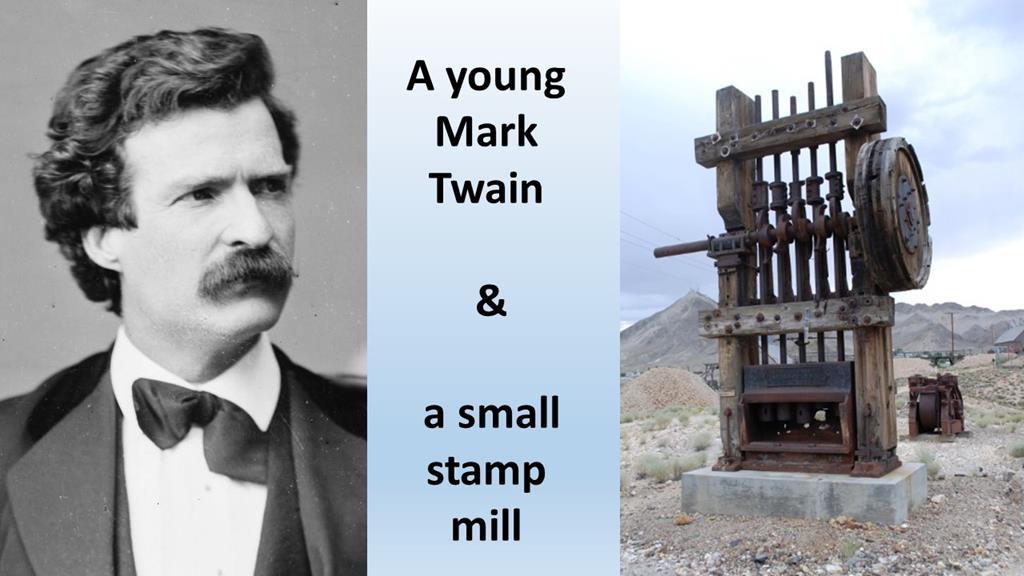

David Lee was formerly the poet laurate of Utah and has been affectionally referred to as “the Pig Poet.” About the time I was leaving Utah, Lee retired as head of the English Department for Southern Utah University. Ever since I left Utah, I have hauled around a large collection of his poetry that came out in 1999, The Legacy of Shadows: Selected Poems. When rereading some of those poems recently, I decided to see if he was still publishing and learned about this volume. It appears that for part of the time, Lee hung out in Silver City, Nevada, a town on the south end of the Comstock Lode (I lived in Virginia City, on the north end of the lode, in 1988-89). Curious, I had the Book Lady Bookstore in Savannah find me a copy of the book for my pandemic reading.

Mine Tailings is divided into three sections: Silver City, the Shaft, and The Ore. In the very first poem of the book, “Silver City Dawn Poem,” Lee touched on many of my favorite memories of the Comstock: pinon fires, the wind, the morning sun, the sage, wild cats and rattlesnakes. As a reader proceeds further into this collection (and especially in the second section, appropriately named “The Shaft”), one comes upon many harsh poems that leaves little doubt as to what Lee thinks about President Trump. Some of the poems, like “On a Political Facebook Posting from a Former Colleague and Friend that Upset Jan,” are discombobulated and fragmented, similar to the President’s tweets. Lee often borrows snippets of Trump’s own words to turn around and challenge him through a poem. The last section of poems contains many poems that are what I considered typical David Lee poems. These contain narrative and dialogue, tell a story and are often quite humorous. One such poem is “Globe Mallow” which is about a flower that Lee and his wife stopped to photograph while driving through a Native American reservation. When a rubbernecking tourist stops and asks what he’s seeing, the man confuses Globe Mellow with marshmallow. The photographer plays along, creating a tall tale about these plants producing marshmallow fruit in the fall. The man drives off, telling his family what he’s learned. The reader is left to humorously image his disappointment when he drives back into the valley in the fall intent on poaching marshmallows from Indian land.

It was good to read some fresh poems from David Lee. I am still pondering the role of the quail (which you had in the Nevada desert, but at least when I was there not to the extent that they show up in Lee’s poems) in these poems. In a sense, the bird is a thread that flies through the various poems.

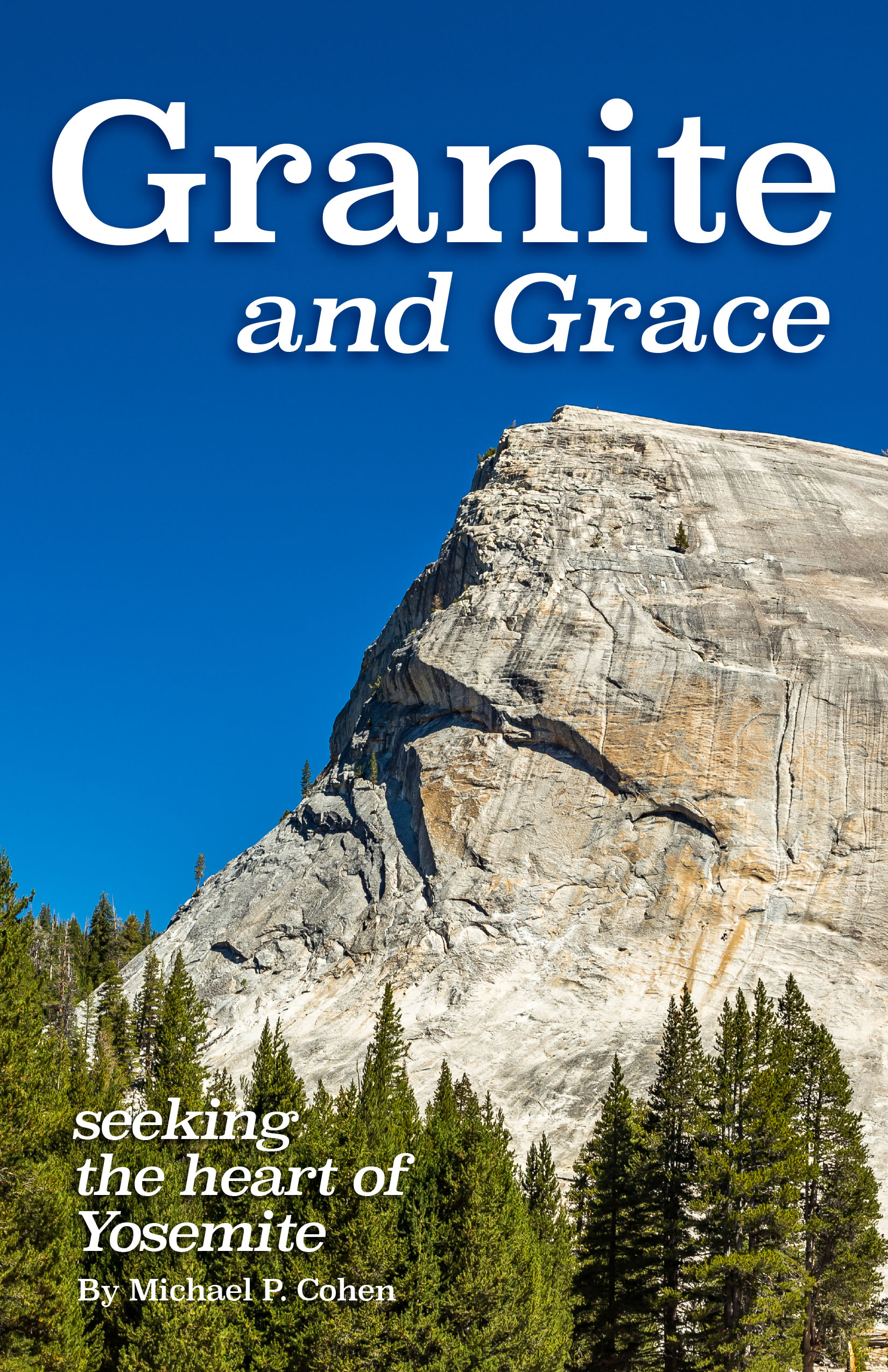

Gary Synder, Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems (Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint, 2009).

I have often heard of Gary Synder and have read a few individual poems and essays of his, but never a full collection. After reading Michael Cohen’s Granite and Grace, a book about Yosemite, I decided I needed to read more of his poetry. The Riprap poems were mostly written in the mid-1950s, about the time when Cohen first visited Yosemite and a year of so before my birth. Synder, as a young man, worked on trail building crews in the park. The title of these poems is appropriate as one often must riprap the side of the trail with rock to prevent erosion. These poems capture the places Synder worked, along with the people with whom he lived and worked. I enjoyed his descriptions of some familiar landscape. The second half of the book is his translations of a seventh century Japanese poet, Han-shan, writings. These poems were also interesting.

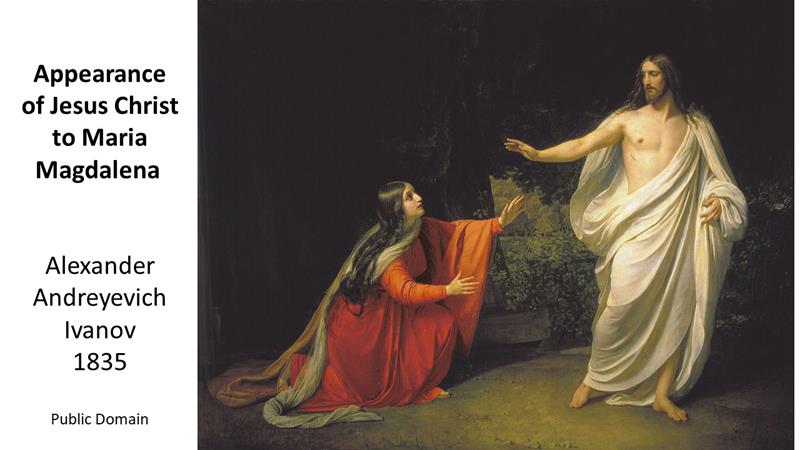

Nancy Bevilaqua, Gospel of the Throwaway Daughter: Poems (Kindle, 2004)

While drawing loosely on stories in the New Testament and other “non-canonical” writings of the first centuries of the Christian era and blending in the setting of the Biblical world, Bevilaqua has written a collection of poetry that area are alive with possibilities. These poems are steeped with a sense of place and often are linked to Mary Magdalene. One can feel the sunrise or the night sky, the parched earth under the midday sun, or the brilliance of stars at night, and the dusty feet from traveling along dirt paths. All these images draw the reader into this world. I appreciated Bevilaqua’s ability to make the reader feel they are present in the first century even though I found myself (against the author’s advice not to read these poems from a religious perspective) wondering about their theological significance. There are certainly poems in here drawn on events of Jesus’ passion. In some ways, these poems attempt to recreate a piece of a lost world, reminded me Alice Hoffman’s novel, The Dovekeepers. In telling the story of the end of the Jewish rebellion against Rome in the first century, Hoffman draws from the experience of four women at Masada. Bevilaqua even has one poem placed at the Battle of Taricheae, an earlier defeat of the Jewish army in their revolt against Rome. Both authors, a poet and a novelist, create a wonderful sense of place at a particular time in history and should be appreciated. I read this collection on my Kindle.

A sapphire dawn, and silver palms. Venus

near the earth

still charred and yet I smell a coming

storm. He is sleeping

on the roof. I am too much awake.

-the opening lines of “Dawn, Migdal”

JEFF GARRISON

Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church

Matthew 15:21-28

August 16, 2020

Last week, we heard about Jesus saving Peter from drowning after he attempted to walk on water. Afterwards, Jesus referred to Peter as one of little faith. Today, we have Jesus referring to a foreign woman’s great faith. What’s up with this? Let’s see… Read Matthew 15:21-28

###

Let’s go back in time to the First Century, to Tyre, a town on the Mediterranean, a port used by the Phoenicians. Like everything else in this part of the world, the town is now in Roman hands. But the roar of the waves crashing the shore are still the same. The taste of salt in the air is still the same. And on this day, as the heat begins to fade and an afternoon breeze from the ocean rolls in, the market opens. As we enter, our eyes catch the vision of a woman shopping. She has come early, before the crowds, her eyes red from crying, to gather food for her and her daughter. She doesn’t speak.

While examining slabs of bacon at the butcher’s shop, she listens in on the gossip. The butcher, a baker and a fisherman are chatting.

“Did you hear that Jesus, you know, the guy who fed 5,000 people with just a few loaves of bread and a few sardines, is in town?[1] A few more stunts like that and I’ll have to sell out,” the baker jokes.

“I might be with you,” the fisherman nods. “The method he uses to catch fish over on the Galilee will put little guys like me out of business.”[2]

The woman lingers, listening and wondering.

“Isn’t Jesus the guy who sent those demons into a herd of pigs causing them to run off the cliff?” the fisherman asks the butcher. [3]

“Yeah, it’s a shame, all that good pork washed out to sea. The price of ribs haven’t yet recovered! It seems the only trade he’s helped has been the roofers.”[4]

“Where’s he staying?” The baker asks.

The woman’s interest is raised, she leans over the counter to hear…

“He had a hard time finding a place after that incident in Capernaum where some people cut a hole in the roof of a house in order to get to him,” the butcher replies. “Finally, Mr. Jones rented his old place up on 2nd Street. I couldn’t believe he’d rent it to Jesus. I asked him about it, but old man Jones’ wasn’t too worried. He said the place needs a new roof and maybe, this way, insurance will cover it.

“I think that’s him coming now,” the baker says, pointing to a crowd gathering at the town’s gate.

Overhearing this gossip, the woman’s face lights up. “Jesus,” she says to herself. “I must meet Jesus.” She drops her shopping bag, kicks off her heels and runs, without stopping, toward the crowd. Pushing through the folks, she shouts as if she’s insane: “Have mercy on me, Lord, Son of David. My daughter is tormented by a demon.” She’s so loud that everyone else stops speaking as she approaches. Even Jesus appears lost for words. The disciples consider her crazy and urges Jesus to send her away. After all, she’s pagan and it would be of no surprise that a pagan’s kid is possessed by a demon. She, too, probably is possessed, they think.[5]

Jesus brushes the woman aside. Pointing to his disciples, he tells her he’s been sent to the lost sheep of Israel. She continues, frantically asking for Jesus’ help. She’s tried everything. Jesus is her last chance for her daughter to be made well. Then her heart sinks, her head drops in shame.

Think about how this woman feels? She’d give her eye teeth to have her daughter freed. When she hears that Jesus is in town, her hopes are raised, only to be crushed. Imagine the pain she felt at this rejection—Jesus being either too busy or too tired to tend to her child. She’s helpless.

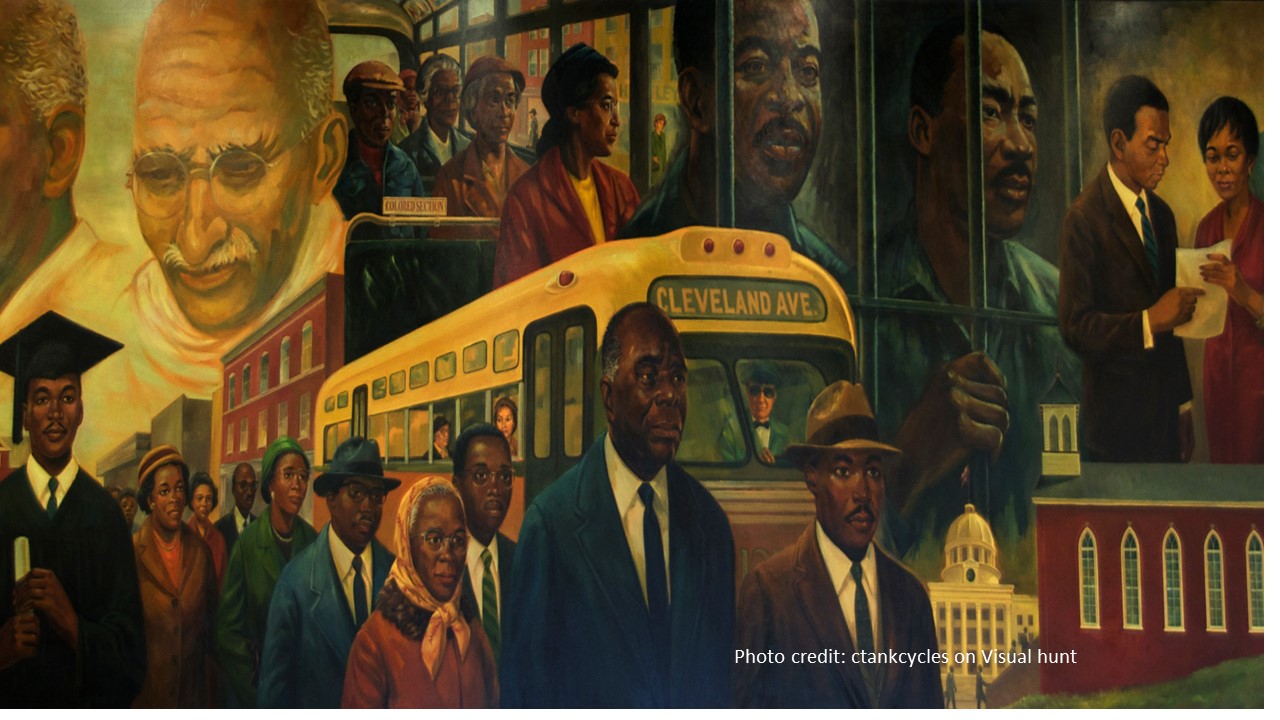

Many of us have felt helpless when dealing with our children. It’s a fairly common among parents, because there are often things beyond our control. But it’s even more common among those who are marginalized. Think of immigrant families risking everything to get a child to America, a place of promise, or to get them out of a place like Syria where the violence is terrible. Or consider African American parents who must have “the talk” with their sons. Knowing that you are not being taken seriously because of your ethnic background is something most of us don’t know about, but there are many such people in the world. Such folks are modern day examples of this Canaanite woman—feeling there is no food at the table for them.

This passage, we all know, is not just about disappointments and bad news. God, through Jesus Christ, is doing something incredible. It actually starts at the beginning of the chapter where we learn that food laws aren’t all they’re cracked up to be. “It isn’t what you eat—what’s in your stomach—that defiles you,” Jesus says. “It’s what’s in your heart.” God’s creation is good. Since we are all created by God, there is a possibility for us to all claim a divine inheritance.

The woman, as are most Gentiles who live near Galilee, is used to being called a dog. Humanity has almost always treated “others” within contempt. It was common in 1st Century Palestine for the pious Jews to refer to the Gentiles as dogs. Yet, I still don’t know what to make of this passage. It disappoints me for Jesus to use such language. I’d prefer to have him say, “My dear child,” or something similar. Just don’t call her a dog, Jesus, but I suppose political correctness wasn’t in vogue during the first century.

But instead of getting hung up on this one word, let’s put this into context and see what Jesus is saying. By saying he has to fed the children before the dogs, we learn Jesus’ mission is first to the Israelites. He’s ministering and teaching to the Jews But knowing this doesn’t help the woman; it doesn’t solve her problem. Jesus is supposed to be a good man and she’s stung by his words.

With her head bowed, I image she begins to leave, then pauses. Has Jesus denied her request? Or maybe, when the disciples are fed, there’ll be something left over for her child. It takes a few moments to get up her courage, but when she does, she spins around like a ballerina, raises her head and looks Jesus in the eyes. “Sir,” she addresses, “even the dogs eat the crumbs from the master’s table.” This lady is bold. Jesus is now going to have to deal with her, one way or the other.

“Even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall for the master’s table,” what a great line.

“You’re right,” Jesus says. I imagine a big smile came over his face as he continued, with a voice loud enough to drive home the point home to the disciples, when he says, “Great is your faith. Your daughter will be healed.”